This story is part of a series of blog posts marking the third anniversary of the court decision that sparked a statelessness crisis in the Dominican Republic.

It’s easy to lose track of the humanity behind the headlines. After the Dominican Republic Constitutional Court’s infamous ruling retroactively stripped citizenship from hundreds of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent three years ago, a complex, highly-politicized crisis unfolded. While many media stories focused on the legalities of the decision, the following vignettes attach faces and names to the people living this nightmare.

Ana Maria Belique

Being an internationally-known civil and human rights activist doesn’t exempt you from humiliation.

Ana Maria Belique—founder and coordinator of Reconoci.do, a movement of thousands of Dominicans fighting to have their nationality and full citizenship rights recognized by the government—found herself under the same awful scrutiny other Dominicans of Haitian descent have faced since the ruling. This summer, while traveling for work, a bus attendant demanded to see her cedula, or national ID card.

“I had to pause and ask the young man, ‘Why are you asking me for my national ID card?’” Ana Maria recounted to AJWS. “It escalated to the point where the driver had to intervene and tell the man to leave me alone. I had to say, ‘Don’t you realize who you’re talking to? Simply by my accent, you should recognize that you’re not talking to a foreigner.’”

Ana Maria said with or without documents, those of darker skin are usually the ones targeted at military checkpoints—but even then, civilians don’t have the authority to ask people for identification. The bus attendant claimed he was trying to avoid “problems” at checkpoints.

“I responded, ‘If that occurs, then that’s my problem, and I will deal directly with them,’” Ana said, adding that the Puerto Rican colleague accompanying her was left alone. “He asked for my documents because I’m black. [My colleague looked white], and they didn’t ask her for any documents—and she indeed was a foreigner! This was complete racial profiling.”

Segregation is alive and well in Dominican society, Ana Maria said: “There are communities where Dominicans of Haitian descent, black people, can’t leave safely—especially in the areas along the border because they fear expulsion or deportation.

“I personally went through this situation,” she continued, “but I’m an activist. I know how to defend myself. Imagine the countless number of young people who experience this but don’t know exactly what their rights are. This limits young people who are afraid to leave their communities because of harassment and profiling—unless they have money to bribe attendants and drivers—which is usually not the case.”

After the 2013 Dominican court ruling, Ana Maria was classified as a member of “Group A”—Dominicans of Haitian descent who were previously documented as citizens. People like Ana Maria, who were already in the Dominican Civil Registry book, were told their nationality would be restored automatically. But the nation’s electoral board leader then “created a new registration book just for Dominicans of Haitian descent,” falsely claiming they hadn’t been citizens at all, Ana Maria said. She is among those being sued to have her original registration annulled.

“It basically establishes segregation,” Ana Maria said. “This creates a lot of legal uncertainty and concern…For example, if I were interested in a political career or running for some sort of office or charge, this status of being a ‘transcribed national’ or a naturalized citizen would set limits to my rights.”

She’s afraid that isolating Dominicans of Haitian descent into one book could make it easy for the Dominican government to do something “with ill intent.”

“I myself cannot even sleep well at night,” she said. “I know that something can happen in the future…and if it doesn’t target me, it can target my future children or grandchildren.”

Felix Marcel

He feared it would happen eventually. It’s not safe for people like Felix Marcel to travel outside of the sugarcane plantations, the bateyes—because in the eyes of law enforcement, they are illegal.

One day, on a long bus trip with his church group from Los Jovillos Batey to San Juan de la Maguana in the western part of the country, his fears came true. Police stopped Felix’s vehicle at a military checkpoint—and pulled him out. Although he had committed no crime, the police detained him. Lawyers got wind of the arrest and had to locate him and bail him out.

“Moving around on his own was a big risk for him,” said Alba Reyes, coordinator of AJWS grantee CEDUCA (“Center for Education and Development”), which works with youth in Santo Domingo’s bateyes and barrios to help them understand and exercise their rights. The 2013 citizenship ruling stripped Felix of his statehood because of his Haitian ancestry, invalidating his birth certificate, national ID card and voting card. A subsequent law that was supposed to automatically restore his nationality didn’t quite work as promised.

“When he went to get his ID card, he was told he didn’t have a right to an ID,” Alba said. “He had to live through that torture that is not having a document to travel freely across your country. If you don’t have documents, it’s like you don’t exist, so you can’t have access to any rights that are supposedly guaranteed by the constitution.”

Felix, now in his early 20s, also couldn’t enroll in high school or travel the three or four miles to the nearest school that enrolled students without paperwork. He wrestled with fear, self-esteem issues and depression.

“We gave him emotional support and worked with him to accept himself as he was—a young man who had rights,” Alba said. “He says that he felt less than the rest of the world, but that through this educational process, he learned that he was a human being with rights, and this empowered him and helped him in the process of getting his ID.”

Felix’s documents came through last year. Only after that was he able to travel, get a job as an auto shop assistant and resume school. “He recently came by CEDUCA and told us he had just applied to work at a new grocery store in Santo Domingo,” Alba said. “And he says he’ll go to university.”

He knows the citizenship crisis is still paralyzing many lives.

“Felix feels bad knowing that others don’t have the same luck, so he participates in the struggle to restore the rights of others,” Alba said. “Because he feels that even though he’s obtained his citizenship, the rights of so many young people like him are still pending. He says that gives him the motivation to work.”

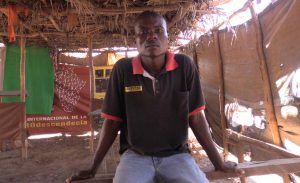

Pierre Paul Eduane

Pierre Paul Eduane, a 27-year-old Dominican of Haitian descent, should have been entitled to Dominican citizenship—but he felt so marginalized in Dominican society as a child that he used travel back and forth to Haiti to attend school.

“There was a time Dominicans were always arguing with Haitians, and there were a lot of fights,” Pierre told Elena Guzman, a Ph.D. candidate associated with AJWS grantee We Are All Dominican conducting research on the border of the two countries. “They hit [and] mistreated Haitians.”

Afraid, Pierre and his family moved to the Haiti border before the citizenship crisis escalated. He has watched other Dominicans of Haitian descent, feeling the effects of the 2013 court ruling, flee in fear of deportation and violence.

Pierre, who’s an ordained Pentecostal minister, thinks it’s a shame that young men who could have “been useful to their country” felt they had to leave.

“It was done in a psychological manner,” Pierre said, explaining that people of Haitian descent have fears that history will repeat itself. In 1937, long-brewing Anti-Haitian politics led Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo to order the massacre of tens of thousands of Haitians. Haitians hadn’t wanted to leave the country back then, either, Pierre said, and Trujillo took matters into his own hands.

Dieudonne Celui and Manuel Celui

Dieudonne Celui, a Haitian migrant who also fled the Dominican Republic and now lives in the same community as Pierre, left his farm because he was afraid that Dominican government officials, police or neighbors would hurt or kill him or his family. His son, Manuel, who is entitled to Dominican citizenship, followed him to the border.

Although their citizenship rights differ, the father and son share the same fears, exacerbated by the aftermath of the citizenship crisis.

“We came here because of menacing [threats],” Dieudonne, Manuel’s father, said. “When the officers came to do the patrols, if we wanted to get some water [from the river], we did so ducking. If we wanted to buy something at the store, we had to crouch. You can’t walk around openly. We didn’t want to be victims.”

Franklin Dinol

A few stories have partial happy endings, thanks to the tireless work of local and international organizations to force the Dominican government to address the statelessness crisis it caused. Franklin Dinol’s is an example.

A Dominican of Haitian descent, Franklin struggled for seven years until he finally received his cedula—his national ID card. “Supposedly, there [had been] an administrative resolution [prior to the famous court ruling] that suspended my documents,” he said in an interview with AJWS grantee We Are All Dominican. “This resolution annulled all my rights as a citizen. I couldn’t work, I couldn’t exercise my right to vote, I couldn’t run for office, I couldn’t travel. It affected me profoundly in my studies.”

But after much perseverance and support from advocacy groups, Franklin eventually received his cedula. And this May, he voted for the first time ever—and even served as an electoral observer, preventing fraud and ensuring elections ran smoothly and ethically.

“I felt happy to vote for the first time,” he said. “I feel like I have the power to choose the people that will be leading the destinies of the municipality and the country. Because of the ID card problem before, we were not able to participate in politics or in decisionmaking.”

But he’s still thinking about his friends, many of whom are being sued to have their documents annulled.

“When I received my cedula card,” he said, “more than joy, I felt indignation. Because even though they were giving me my ID, I knew that many others were still being denied their documents.”

The work of AJWS’s partners to ensure that all people affected by the crisis are able to access their rights is far from over.

María José

It wasn’t until this May, when María José exercised her voting rights after receiving her ID card, that she felt human.

“I feel like a person,” she said on election day in a video interview with AJWS grantee We Are All Dominican. “Like a human being, embraced by my flag.”

For 10 years prior, María, who is a Dominican of Haitian descent, was repeatedly denied the national ID card she needed to register for college, obtain a passport and vote. “If you don’t have the right to choose who is going to govern you, then who are you?” she opined. “It’s like we don’t have a flag.

“They said my last name sounded French, that my parents were Haitian,” she said. “That’s been the trajectory of my life, until today.”

Ignacio Gabriel

A career in sports could be Ignacio Gabriel’s ticket out of the batey his family often stays in. He’s so talented that two Major League Baseball teams—the San Diego Padres and the Kansas City Royals—have offered the teenager contracts to play professionally. But he couldn’t produce the proper identification needed to sign.

Scarsdale Rabbi Jeffrey Brown, a member of AJWS’s 2015-2016 Global Justice Fellowship, met Ignacio on a trip to the Dominican Republic earlier this year. Ignacio told his new American friend during that visit that even though he was born in the country and grew up there, his parents’ Haitian heritage had prevented him from ever getting the documents that would make him a Dominican citizen. The Junta Central Electoral (Dominican electoral board) repeatedly told him they couldn’t help and insisted that he approach the Haitian Embassy to get his Haitian papers.

“But, of course, Haiti does not know that Ignacio exists!” Rabbi Brown said.

Ignacio and his mother and three brothers feel forced to hide in a batey community to avoid immigration authorities—and deportation. Rabbi Brown says Ignacio is being “punished because [his] skin is a little darker and [his] voices carries an accent. Ignacio’s story and the stories of so many others who remain [disenfranchised] in our world, deserve to be told. Ignacio deserves to be counted.”

Juan Telemin

Problems obtaining nationality documents stunted Juan Telemin’s future for nine years—but now, he’s enjoying more opportunities. After finally receiving his cedula in 2014, he voted for the first time this May—for himself.

Juan, a Dominican of Haitian descent, ran for mayor of his municipality, Guaymate, in the province of La Romana. He is a member of Reconoci.do, an advocacy organization supported by AJWS.

“I got into politics because I understand that it’s time for Dominicans of Haitian descent to assume our responsibility to be the change we want to see,” he said in a video produced by AJWS partners We Are All Dominican and Reconoci.do. “If we want to see our integration, we have to realize that we…have to promote that integration. If they don’t give us that space, we have to break those barriers. We have to disrupt until the moment they give it to us. Most of what has happened to us as a social group has been precisely because we don’t have anyone to represent us, no one to make decisions on our behalf.”

Juan didn’t win the election, but he’s proud of what he did accomplish.

“I embody many of the conditions that are cause for rejection in this country—being young, being from a batey, being the child of a Haitian migrant, being poor,” he said. “For this reason, taking on this challenge has been daunting. But at the same time, it’s been cool. I’ve been campaigning for two, three months. As someone with all those characteristics, I don’t have the sympathies of 100 percent of the population—I wouldn’t even dare to say 50 percent. But if people accept my candidacy, if they say ‘I’ll support you,’ if I even get five votes, just five votes, I will have achieved something that has not been done in all of the history of the Dominican Republic.”

And he got a kick out of voting for himself.

“I hope to be able to vote for myself again!” he said. “Or I’ll vote for someone else. But I’ll take with me the pride that the first face I marked to vote for mayor was my own. That is priceless.”

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.