Just Thought is a series of essays from AJWS applying Jewish wisdom to the pursuit of tikkun olam today. Drawing upon Jewish history, Torah sources and the latest headlines, we plumb pressing questions about human rights and global justice from a Jewish perspective through monthly essays by noted scholars, activists and AJWS staff.

Last year, when I visited Kachin State, a mountainous region at the northernmost tip of Burma, I couldn’t help think that the women activists I met there, thousands of miles from my home, reminded me of my late grandmother—and a revelatory evening we spent together in the summer of 1975 conversing in Yiddish.

These Kachin women, members of one of Burma’s many persecuted ethnic minorities, shared their love of the Kachin language, their resentment of pressure from the central Burmese government and military to abandon their culture, and their desire to live in a society that guarantees democratic rights for everyone and encourages all ethnic cultures to flourish. I was struck by how similar their views were to those of my grandmother, who had explained to me during that conversation in 1975 why she joined the Jewish Labor Bund, a democratic socialist Jewish party, at the turn of the 20th century.

In 1975, at age 18, I had begun studying Yiddish at the YIVO Institute and Columbia University. On a class trip, I bought a record album of Yiddish labor songs and decided to play it for my father’s mother. I had no idea how she might respond to it, as I actually knew very little of her life story. To my great surprise, as the recording played the Bund’s anthem, Di Shvue, my grandmother joined in: “Brider un shvester fun arbet un noyt—Brothers and sisters, workers in need.”

Exuberantly, she sang the lyrics of this and other revolutionary Yiddish songs that had been stored in her brain for 70 years, sometimes even adding lyrics not recorded on the album. As she sang, she shared stories from her life, speaking in Yiddish, a language in which we had never conversed before. Communicating in her mother tongue inspired her to share more of herself with me than she ever had done in the past in her more limited English.

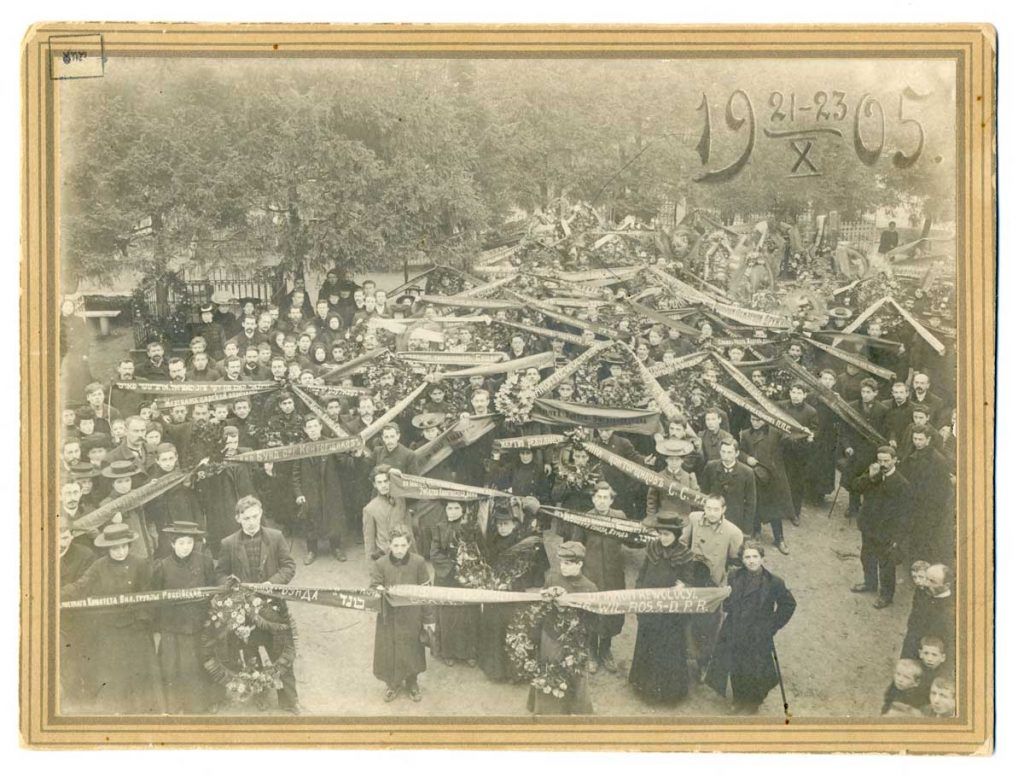

That evening, I learned that she was born to Hasidic parents in the 1890s in Belts, a town then located in the Russian Empire. She and her brothers rebelled against traditional Jewish life and the tsarist political order and joined the Bund. My grandmother explained that she had sung some of the songs on my new album in the woods outside of Belts with other radicalized Jewish youth. She shared that she did this on May Day, the international workers’ holiday, during the 1905 Revolution, a wave of social and political unrest aimed at overthrowing the tsars.

Founded in Vilna in 1897, the Bund offered a political vision avidly adopted by modernizing socialist Jews across Eastern Europe and in immigrant communities around the world. The Bund became a champion of secular Yiddish culture, as well as one of the most influential political parties in Jewish life before World War II. This was especially true in Poland, where the Bund opposed the twin threats of anti-Semitic, right-wing nationalism and totalitarian Stalinist communism. The Bund affirmed that Jews—like all peoples—had the absolute right to live and to express their cultures wherever they found themselves.

The Bund’s philosophy of doikeyt—literally, “here-ness”—was central to its vision of a just world. Bundists opposed states dominated by one ethnic group and believed that all people had the right live in democratic, multi-cultural societies, enjoying both equal rights and cultural autonomy—that is, the right to express themselves in their languages and cultures without pressure to abandon them. To build its following and create a modern, progressive Jewish culture, the Bund established unions, secular Yiddish-language schools, newspapers, summer camps, health centers, sports teams and much more.

Listening to the Kachin women I met in Burma and other ethnic minority activists around the world whom AJWS supports, I have noted time and again that they share much in common with my late grandmother’s vision of the world. From Burma to Guatemala to Senegal, these women of different ethnicities and indigenous groups affirm their cultures and languages, even as they face pressure from dominant cultures to abandon them. These activists fight for a world that affirms difference and diversity while guaranteeing full human rights for all: the right to organize for change, including unions and political parties; the right to vote in free and fair elections; the right to work without exploitation; and the right to live free of hate, state-sanctioned violence and genocide.

In 1913, my grandmother left Belts for New York, where she raised my father and his two brothers, mostly in her native language—Yiddish. In New York, she joined a union organized by Yiddish socialists that won battles for fair wages and safe working conditions and in whose ranks she marched on May Day each year in Union Square. One of the most moving Yiddish songs she sang to me that evening in 1975 is “Arbeter Froyen,” a stirring plea for working women to join the movement to build a better world:

Working women, suffering women … Why do you stand on the sidelines?

Why don’t you help us build a temple of freedom and human happiness ….

More than once, brave women have made tyrants … tremble.”

The sound of my grandmother singing these words will always inspire me and remind why I, the grandson of a Bundist, work as a member of the AJWS community to build a more just world.

Enjoy this 2016 recording of Arbeter Froyen performed by Sarah Mina Gordon and Daniel Kahn from an unmastered roughmix that will be released in 2017 on a forthcoming album by Daniel Kahn & The Painted Bird. The original Yiddish lyrics were written by David Edelstadt and the new English lyrics are by Daniel Kahn.

Send your thoughts, questions and feedback about this piece to JustThought@ajws.org.

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.