Long before it became his life’s work, the fight for human rights had already taken root in Tawanda Mutasah — a lesson first given by his mother, who taught him, “Every person matters. Take them all seriously.”

Drawing on language from Genesis 1:27 — “God created humankind in the Divine image” — his mother’s plain-spoken wisdom guided Mutasah on a journey that, in February 2026, brought him to American Jewish World Service (AJWS) as its new president and CEO.

“Though a simple formulation, from a devout woman who in the segregated world of her upbringing lacked educational opportunities,” he said, “It was a classic rendering of the ideas and values that we think about when we talk about the Jewish belief of b’Tzelem Elohim — the essential dignity of every human being. It made it clear that human rights matter, that human dignity matters. And it deeply impressed, even kind of surprised me at first, that she not only wanted better opportunities for me specifically, but was almost as equally preoccupied with my obligations to neighbors who were equally trapped by the indignities of our life.”

For AJWS, which this year celebrated four decades defending marginalized voices, Mutasah’s arrival is fortuitous. His expertise, gained in global leadership roles at peer organizations like Oxfam America and the Open Society Foundations, is rooted in a boyhood spent on the margins.

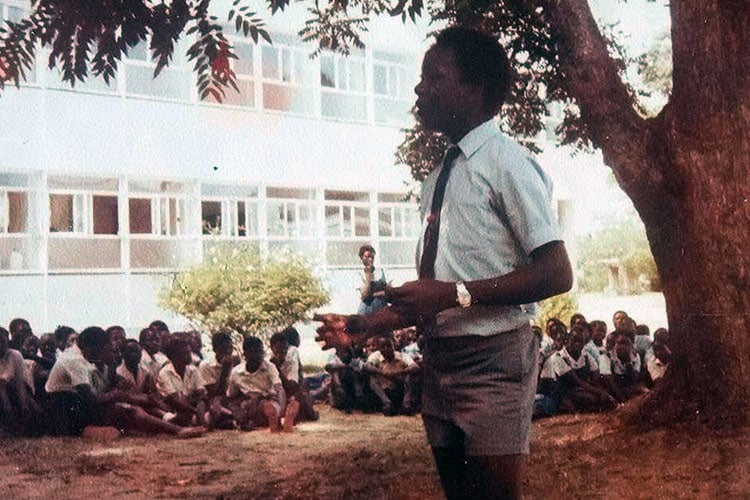

Convictions from His Youth

Mutasah grew up in the provincial capital of Masvingo in southeastern Zimbabwe. At the time, Masvingo was a segregated town. A river ran between the haves and the have-nots, organized on racial lines — a reality that did not escape his notice. On one side, streets were safer, roads were paved, and schools were well-resourced; on the other, the ghetto of Mucheke, where Mutasah was born, sewage flowed in the streets, schools were overcrowded, and children dressed in rags, often going without shoes.

“From the outset, it was clear to me that inequality was fundamentally structural,” he said. “That compelled me to be concerned about everything I saw, to wonder about it, to ask questions about it.”

Even at age 9, Mutasah could see the injustices that, decades later, mirror the human rights struggles AJWS and its grantees combat today. Parents forced female classmates into child marriages; neighborhood men beat their wives brutally; gender-based violence was pervasive.

By the time he was a teenager, there were signs of improvement around him. In fact, a few years after Rhodesia gained its independence and became Zimbabwe, students from his ghetto school could rent space at a former white school across the river. He recalled being a 14-year-old boy and giving a speech there on Commonwealth Day. However, injustices persisted.

While he admits that structural inequalities lie at the root of these problems, solving them is not our only task.

“We must look at the structural issues but at the same time, each of us must look inward and ask, ‘what can I contribute?’” Mutasah said. “I’m firmly convinced that structural realities do not absolve me from taking responsibility for what I can do better.”

Those lessons fueled a lifelong desire to tackle injustice. He studied law at the University of Zimbabwe, at the same time immersing himself in the student union and eventually stepping into a leadership role. But that activism came at a cost. He was expelled for his involvement, tortured, and forced to flee to South Africa to continue his studies, experiences that hardened his resolve.

“I still carry the fire in my belly that I had then — the conviction that struggles for human rights are necessary, that they are part of our agency and our moral commitment as human beings.”

This conviction has guided Mutasah’s decades of work across the human rights, development, and humanitarian sectors where he has led programs in civil and political rights, economic and social rights, climate and environmental justice, gender and racial justice, and humanitarian law — areas familiar to the AJWS community.

When Mutasah first encountered AJWS, he saw alignment beyond its programmatic mix: in the people, the values, and the model. “Joining the team,” he said, “seemed beshert” — “destiny” in Yiddish— as AJWS’s values resonate deeply with his own.

Mutasah noted that AJWS’s commitment to tikkun olam — repairing the world — complements his own understanding that humanity is bound together. That AJWS’s mission is informed by Jewish experience and moral courage embodies what Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel called “praying with my feet.”

“The idea we can ‘pray with our feet’ as an organization founded in Jewish values and commitments is part of the strength of AJWS,” he said.

Now is the Time

With human rights under assault globally, moral courage is needed more than ever. From rising authoritarianism to escalating violence against LGBTQI+ communities, from the pain of communities seeing their rivers contaminated by rapacious extraction to rollbacks on reproductive rights, Mutasah called out an alarming degeneration of the post-World War II order that speaks directly to the way AJWS operates.

“In a context like that,” he said, “AJWS’s work is cut out for it. We are in a moment where the historical infrastructure of norms and values on which we once depended is being torn asunder.”

AJWS knows this shift up close. In 2025, following the federal government’s shutdown of USAID, one in five grantee partners lost 30 percent or more of their funding — some 99 partners. Thirty-one of those lost more than 50 percent of their funding. In addition, public policies that helped grantees thrive are being rewritten by the United States as well as by the countries where AJWS works, thwarting the grassroots organizing that grantees do so well. Now is the time, Mutasah argued, for civil society to unite and draw on the wellspring of ideas, principles, and moral leadership of their communities, and act as a unified front.

“I know that solidarity matters because I have myself been on the receiving end of state brutality when I was a student leader in Zimbabwe,” Mutasah said. “I’ve known what it means to struggle for human rights and to work to your convictions about human worth and dignity and face the brutality of those that hold power — and sometimes as you turn around looking for solidarity, looking for support, you may not find it.”

In this moment, AJWS must help renew and revitalize the global vision of human rights, restore momentum in local struggles for justice, and win new allies among those who feel discouraged and yet are ready to make change. He points to long-term support of grantees, in-country staff working closely with local activists, and dogged advocacy in D.C. as key to building the infrastructure that will withstand, and eventually overcome, the backlash against human rights.

“In addition to the deeper impact we will seek in the Global South, at a moment when our mission could not matter more, AJWS also offers our communities of conscience here in the United States something larger to reach for — the chance to serve as ambassadors of justice to the world, walking today with our partners in the Global South just as Rabbi Heschel walked with the civil rights marchers here in the United States.”

And, as always, he is leaning on his mother’s wisdom to meet the challenges ahead.

“She was my first inspiration for understanding that hope is actually the currency that one uses to come out of difficult situations and circumstances,” Mutasah said. “It is not bitterness. It is not resentment. It is not anything else but hope. Hope itself can be a radical proposition.”

In that spirit, Mutasah believes, the path ahead is clear: “Let us go forth — our mission beckons.”