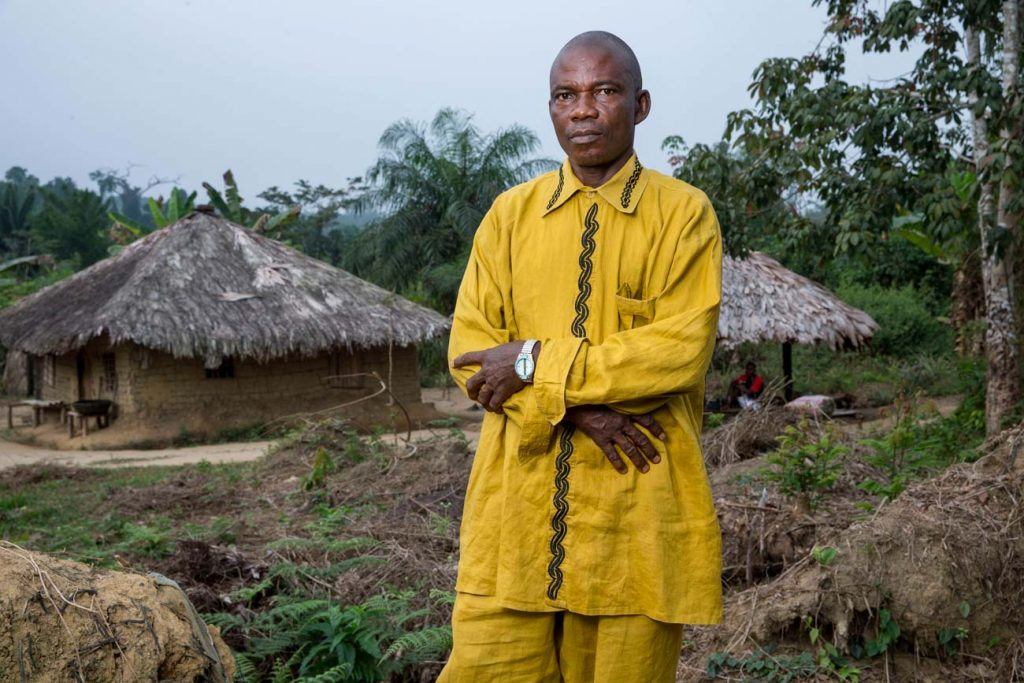

“Even if you were to bring guns and machetes, we would still stand for our land. We would not fight [you]…but we would face you non-violently, and we would stand…You will not take [our land].”

That’s the message Joseph Cheo Johnson—a chief elder in Grand Bassa County, Liberia—has for anyone seeking to claim the land upon which his people have lived for generations. And judging by his clan’s success in preventing a powerful multinational company from expanding onto their territory, he means it.

***

Standing over 6 feet tall and dressed in his traditional regalia, Chief Elder Cheo cuts an imposing figure during a village meeting in Blayah Town, Liberia. Speaking emphatically in Bassa—the name of both the local dialect and his people’s tribe—he has the air of a strict parent imparting an important lesson to his children. But then Cheo’s stern expression softens, his face collapses into a broad smile, and he begins to lead the group in song and dance.

A proud and strong leader, Cheo also sees himself as one of his people, and takes his job of defending their interests very seriously—a commitment that has earned him widespread trust and respect.

Protector of the Land

Born in Blayah Town in the late 1940s, Cheo is a member of the Jogbahn clan, part of Liberia’s larger Bassa tribe. As chief elder of District #4 in Grand Bassa County, Cheo oversees around 38,000 people hailing from 10 different Bassa clans, including the Jogbahn. A traditional leader whose local authority is recognized by the Liberian government, one of Cheo’s most important responsibilities is to act as the guardian of his people’s land.

Under Liberia’s progressive land policy, individuals, families and communities have legal rights to their ancestral lands, even if they don’t have documentation to prove it. But in a country where illiteracy is high, access to legal aid is limited, and foreign companies and elite politicians wield enormous power, these customary land rights are often ignored or trampled upon.

Some communities refuse to stand for this abuse. In 2012, when the British-owned company Equatorial Palm Oil (EPO) came to ask Chief Elder Cheo if it could expand its plantation onto his people’s land, his answer was a clear, concise and unequivocal “no.”

“I told them, ‘We [cannot give you our land] because we have nowhere else to go,’” Cheo recalled in an interview with AJWS last January. “This land is very, very important [to us]. This is where we get our food, the water we drink…the herbs we use…Those are the things we survive on.”

A People United

One need only spend a day in Blayah Town to see that Cheo is not the only one with strong feelings about the land.

“This land is life,” Blayah Town women’s leader Teresa Davis explained. “We are illiterate…So the only thing we depend on is the land. [We] farm…[to earn] money so that our children…can go to school and be somebody tomorrow.”

Another Blayah Town resident described the land as their “supermarket”—a source of not only sustenance like cassava, potatoes and palm oil, but also free medicinal herbs that can treat common illnesses. Yet another said the land was a legacy for their children.

Finally, there’s the fact that the land ties the Jogbahn people to their past—a connection made visible in the local burial grounds. “When something bothers us, we can go…to [the graves] and talk to our ancestors,” Cheo said. “That is very important.”

In Search of 20,000 Acres

Although the Jogbahn refused EPO’s request to expand onto their land, the clan did not have a problem with the existing EPO plantation, which spans nearly 14,000 acres. Originally run by a company called LIBINC, the plantation flourished from 1965 to 1989, producing barrels upon barrels of palm oil—a vegetable oil derived from the fruit of oil palm trees, and used in commercial products ranging from packaged baked goods to lipstick to laundry detergent.

In 1989, a bloody civil war erupted across Liberia, and LIBINC was forced to suspend its operations. The conflict finally ended in 2003, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was elected president in 2005. Arguing it would help spur economic recovery, President Sirleaf signed away vast tracts of Liberia’s land to foreign industrial agriculture and mining companies. In 2008, her government ratified a contract granting EPO the rights to the old LIBINC plantation for 50 years, and promising the company over 20,000 additional acres in Grand Bassa County. But the location of these acres was not determined, so EPO began knocking on the doors of local community leaders in search of them. Chief Elder Cheo was one of these leaders.

Peaceful Protest, Violent Crackdown

Unfortunately, EPO didn’t take Cheo’s “no” for an answer. In September 2013, despite the clan’s objection, company officials crossed from the existing plantation onto Jogbahn land. According to Cheo, the EPO team was measuring—or “surveying”—the land, with plans to plant oil palm trees on it.

Cheo immediately dispatched some 250 Jogbahn men to the survey site, where Garmondah Barwon—their spokesman—asked the EPO team to leave. At first, the company honored the men’s request; but two days later, the surveyors returned. So the clan decided to march to Buchanan, the county capital, to seek assistance from their superintendent. Not long into their march, they were intercepted by EPO security and officers from the Police Support Unit (PSU), the armed wing of the Liberian police force.

“When they saw me, they said, ‘This is the speaker…Let us handle him’…and they beat me badly,” recalled Garmondah, who said that EPO security officials kicked, punched and tear gassed him while PSU officers stood by. “They said, ‘You are an elderly man, why do you gotta stop development?’”

Garmondah’s attackers loaded him into their trucks along with 16 other demonstrators. But when they reached Buchanan, the county attorney ordered their release, asserting that the men had a right to meet with their elected officials.

Sounding the International Alarm

By this time, word of the Jogbahn’s predicament had reached the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI) in the Liberian capital of Monrovia—a leading Liberian land rights organization founded in 2002 with the goal of ensuring communities have a say in government and corporate dealings that affect their natural resources. Recognizing the key role SDI plays in safeguarding the land rights of Liberians, AJWS has supported the organization since 2011.

When they heard about the crackdown on the Jogbahn demonstrators, SDI reached out to the clan and offered their assistance. As their first order of business, SDI conducted an in-depth investigation into the Jogbahn’s case, concluding that EPO had violated the clan’s customary land rights. Based on these findings, in October 2013, SDI submitted a formal complaint on behalf of the clan to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO)—an international body that regulates the global palm oil trade, and of which EPO is a member.

The complaint threw the Jogbahn’s struggle into the international spotlight, prompting a team from the international watchdog group Global Witness to travel to Liberia to perform its own investigation. Global Witness found EPO to be at risk of violating of RSPO principles regarding the land rights of local people. The pressure on EPO was mounting, but the Jogbahn’s battle was far from over.

Empowering the People to Speak Out

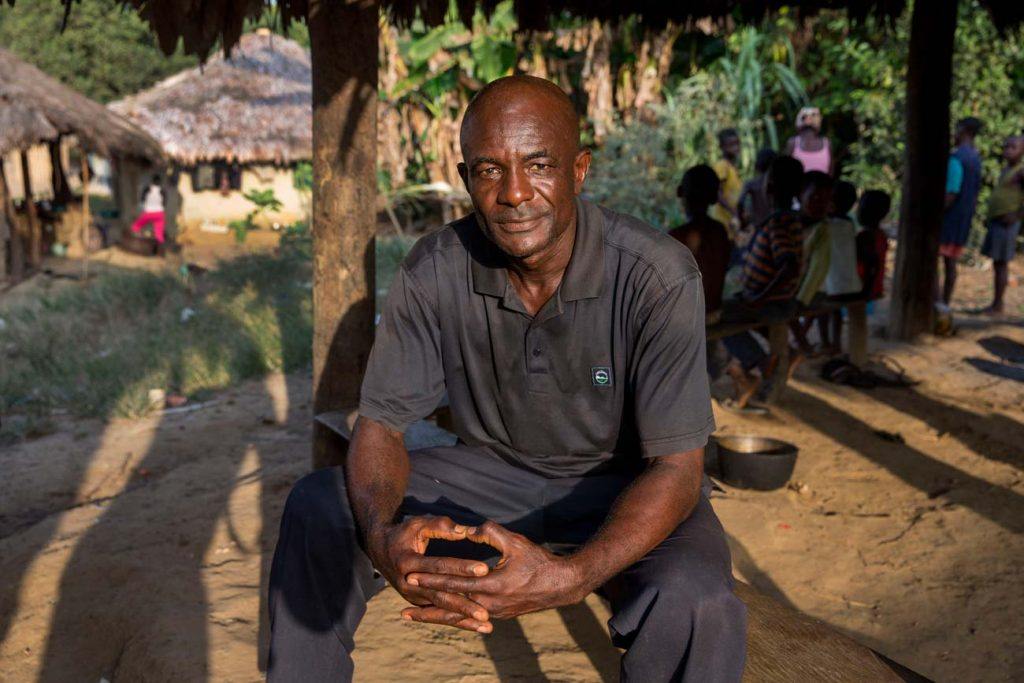

As they awaited a response from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, SDI began to educate the Jogbahn about the land rights guaranteed to them under Liberian law, and to explore the various non-violent means they could employ to stand up for themselves. According to SDI’s local representative, Nelson Tarr, between 2013 and 2015, the organization provided more than 20 workshops to the clan.

“SDI taught us about land rights [and] made us understand that we can [choose to] consent or not consent [to development companies],” Nelson said.

Among the most important things SDI did for the Jogbahn was to help the clan mount an effective advocacy campaign against EPO. An impoverished people with limited access to transport, Jogbahn community members were eager to attend trainings and promote their cause in Buchanan and Monrovia, but they lacked the means to get there. With funds from AJWS and other donors, SDI was able to transport up to 40 people at a time to attend workshops and meet with EPO and Liberian officials—including President Sirleaf herself in March 2014.

Securing Presidential Back-Up

Chief Elder Cheo recalled that in the meeting with President Sirleaf, the Liberian leader asked him if he was against EPO. “I responded, ‘No, I did not say I’m [against] the company…I’m saying the land they have is enough…they should stop there.’ Then the president said, ‘Okay, what you’ve said is true. We are going to write to EPO and tell them to stop.’”

In defiance of the president’s orders, EPO began clearing bits of Jogbahn land at night—specifically a forested area that borders the company’s plantation.

“We got very angry,” said Cheo. “We told them if they do it again…we are going to go back to Buchanan and…[tell] the authorities.”

Apparently, EPO decided clearing the land was not worth trouble with the Jogbahn or the government, and stopped its activities.

The Long Road to Victory

In June 2014, nearly nine months after SDI submitted the complaint on behalf of the Jogbahn people to the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, RSPO representatives sent a team to Liberia to assess the clan’s allegations. The body spent the next year deliberating the case, finally publishing its findings in June 2015. The roundtable concluded that there were “reasonable grounds to believe” that the land EPO was seeking to develop belonged to the Jogbahn people, and gave the company one year to resolve all issues surrounding their apparent attempted land grab.

To settle their dispute, EPO and the clan agreed to conduct a joint mapping of the plantation’s existing boundaries and the Jogbahn’s communal lands. To facilitate the exercise, SDI trained Jogbahn community members on the use of GPS technology. The joint mapping was successfully held on January 27th, 2016. EPO accepted the boundaries outlined by the Jogbahn people and submitted its fourth and final report to RSPO on July 7th, 2016—marking the end of the clan’s three-year long struggle.

Words of Gratitude

While the Jogbahn’s victory over EPO would not have been possible without their unity and determination as a people, the clan is the first to note SDI’s equally vital role in their success.

“If it were not for SDI, we wouldn’t be on this land,” said Lucy Zor, who credits SDI with maintaining peace. “EPO came here, they beat up our husbands….but [our husbands] are still alive. If we had not listened to SDI….not to use violence, then it would have been different.”

Borbor Glagbo compared the Jogbahn’s story to the Israelites being freed from slavery in Egypt: “We are getting out of slavery [from EPO], with SDI’s help.”

Their gratitude notwithstanding, Chief Elder Cheo is concerned that his clan is now viewed as “anti-development” by the Liberian government. He says local representatives visiting the area routinely skip Jogbahn towns, and he fears that this will prevent them from benefiting from vital government projects such as schools, roads and clinics.

Whatever the future brings, Cheo can rest assured that SDI will stand with him and his people—and that AJWS will be right there beside them.

All photos by Jonathan Torgovnik

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.