Two years ago today, on March 30, 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared an Ebola outbreak in Liberia—one of the 19 countries where AJWS works. The virus entered the country from neighboring Guinea and made its way to the densely populated capital of Monrovia in June of 2014, igniting a crisis that would claim nearly 5,000 Liberian lives.

AJWS had its finger on the pulse of the outbreak from day one. When Ebola hit Montserrado County—seat of the nation’s capital and home to a quarter of its four million people—we began discussing a response with our local Liberia representative and the 16 Liberian organizations already receiving AJWS funding. We issued an emergency fundraising appeal and our supporters donated over $1 million to stop the spread of the brutal virus, which kills up to 90 percent of its victims. We channeled this money to 22 Liberian groups working on the frontlines of the response.

In the coming weeks, we will pay tribute to these courageous organizations, which played a major role in stemming the tide of Ebola in Liberia. We begin with the National Imam Council of Liberia (NICOL), which taught people of all faiths how to protect themselves from the virus and supported those whose families were decimated by the epidemic.

In June 2014, a well-known doctor in Banjor, a community near the Liberian capital of Monrovia, died suddenly of a mysterious illness. A devout Muslim, the doctor was buried in the traditional way: imams washed and blessed his body then carried it to a site near the local mosque for burial.

Within days, all five of the imams who bathed the doctor’s body were dead. One by one, those who came into contact with them also fell ill—and one by one, they died. In a country where malaria, typhoid and a slew of other sicknesses kill thousands of people each year, it was difficult to determine what was happening. But one thing was abundantly clear: something was killing people in Banjor at an alarming rate, and Muslims were getting hit the hardest.

“Muslims were dying more than any other people, along with health workers,” recalled Imam Abdullah Trawally, who co-leads a mosque in Banjor. “I was very afraid, but … decided to help … because … people were looking up to God, and after that, they were looking up to us [the imams].”

On the frontlines of a deadly outbreak

Imam Trawally had heard about Ebola in the news. Realizing the virus was likely behind the growing death toll in his community, he mobilized several fellow imams and launched a homegrown awareness campaign.

“I talked to one of our Muslim brothers [who] has a car. I told him to lend us the car … so we can move around the district … to educate people about Ebola,” he explained.

The imam’s efforts were critically needed: At the outset of the outbreak, many Liberians doubted or even denied the existence of Ebola. Their skepticism was rooted in a deep mistrust of government officials and, in some cases, foreign aid agencies sounding the alarm on the virus. In this context, trusted local leaders like imams were able to break through doubt and denial where others could not.

Armed with a basic knowledge of Ebola and a PA system to amplify their voices, the imams drove from community to community, warning people about the virus. They told residents of all faiths that Ebola was causing scores of deaths in the area and advised them to wash their hands frequently to prevent it from spreading. They also cautioned their Muslim brethren against burying their dead in the traditional way. This advice was key to curbing fatalities in the Muslim community, as Ebola spreads through infected bodily fluids, making the corpses of its victims hotbeds for the virus—and explaining the heightened death tolls among Muslims.

Impressed by the imams’ initiative, a doctor working at the country’s main medical center held a training for Muslim leaders and Banjor community members of all religious backgrounds. The trainers advised Imam Trawally to record the names and addresses of all the children orphaned by Ebola in the district. This documentation opened doors for the children to receive potentially life-saving benefits, including rice distributed by the World Food Program (WFP).

An Ebola awareness campaign for people of all faiths

While the imams of Banjor were working around the clock to save their community, the National Imam Council of Liberia (NICOL) was organizing a nationwide awareness initiative that AJWS would later fund. A governing body that oversees some two to three thousand imams in all 15 counties of Liberia, NICOL plays a critical leadership role in Liberia’s Muslim community, which represents some 12 percent of the population.

“Imams are … like a counselor, they are people who can talk not only to Muslims … but to … [all of] humanity,” said Imam Harouna Kabbah, the financial secretary of NICOL. “If a community imam says something has to be done, everybody respects that, and everybody listens.”

Recognizing the urgent need to act, NICOL convened a group of Islamic scholars and medical experts to figure out how to stop Ebola in the Muslim community. They developed awareness messages that used teachings from the Koran as tools to convince Muslims to protect themselves from Ebola and trained imams, including Imam Trawally, to spread these messages in Ebola hot spots.

“According to our prophet [Mohammed] … you should not put your hand in something that will destroy you. So if sickness comes, you should [stay away],” explained Imam Alhaji Folley, who led Ebola awareness trainings for imams in Bomi County. NICOL used this and other Koranic teachings to assure followers that it was okay to forego certain practices during the Ebola crisis, such as washing the bodies of the dead, and to reinforce key public health warnings issued by national and international health authorities.

The NICOL support gave Imam Trawally and his peers—including Sheikh Abbas Kanneh, the highest-ranking imam in Banjor who coordinated the NICOL response there—a much-needed boost in their outreach. “Ebola started reducing in September 2014,” Imam Trawally said. “At that time, people were informed; down to the small, small children, they were informed.”

The post-crisis crisis: AJWS steps in to help

By early 2015, reported Ebola cases in Liberia had dropped from hundreds to less than a dozen per week, and the WHO declared the country Ebola-free on January 14, 2016. But the after-effects of the crisis—which has left thousands of orphans, widows and widowers in its wake—are profound.

NICOL witnessed this devastation firsthand and wanted to help, but their resources were stretched thin. Dependent on small contributions from the mosques in their network, the council had little means to continue their activities. That’s when AJWS, which was already supporting a number of other groups working on the Ebola response, stepped in to help. In May 2015, we delivered a grant to fund NICOL’s efforts to assist children affected by Ebola and provide refresher trainings for imams in three hard-hit counties.

“I was very happy because our people received … assistance … I was very grateful. First to God, then to AJWS,” said Imam Kabbah, who confirmed that the AJWS grant was the council’s first and only source of international support.

“Everybody would have died without the Imam Council,” Zainab Kanneh said of NICOL. Zainab’s brother and sister-in-law died of Ebola; she is now caring for their sons, 10-year-old Vamuyam and 11-year-old Kabuneh. “They [NICOL] have been doing well for us because they’re the only ones who have helped us up until today.”

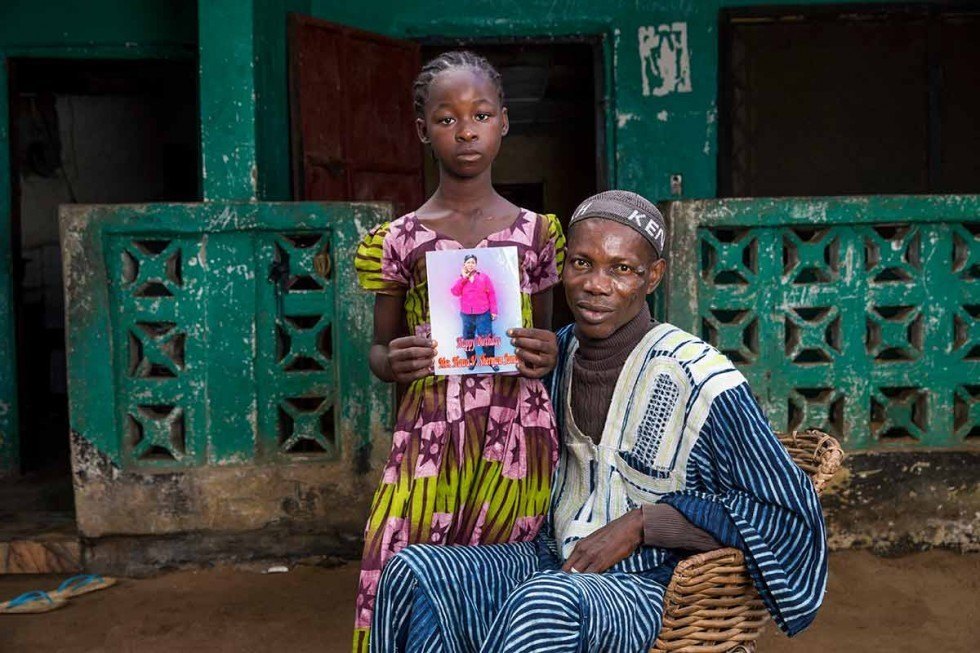

“[Without NICOL], things would have gotten much worse,” echoed Mohammed Samah, who survived Ebola with his 11-year-old daughter, Watta, but lost his wife to the illness.

There for the long haul: NICOL’s commitment to humanity

The scars of Ebola, which continues to rear its head periodically in West Africa, are far from healed.

“People say that Ebola is finished in Liberia, but we do not want the world to forget about us,” said Mohammed, the Ebola survivor and widower from Banjor. Mohammed has been unable to return to work since his recovery. “We are still appealing on behalf of all, for people to help us.”

NICOL is committed to supporting people like Mohammed for the long-haul. “The children still need help,” said Imam Kabbah. “And the awareness needs to continue… because… Ebola can come back. We hope the imams that were trained… will continue to live by the training… for the betterment of humanity.”

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.