Ebola from the front lines: AJWS’s Liberia consultant reflects on the crisis and AJWS’s work to stop it

Dayugar Johnson (“D.J.”), AJWS’s in-country consultant in Liberia, imposed a quarantine on his family soon after the Ebola epidemic

struck their neighborhood in Monrovia last year. He was especially strict with his children.

“If you leave,” he warned them, “don’t return for 21 days!”

When they needed groceries, D.J. drove his wife to avoid taxis, which proved a dangerous virus transmission source. They only left the house dressed in long layers of clothing and armed with bottles of diluted chlorine to sanitize their hands. The kids couldn’t play with the neighbors, and hand-washing became ritualistic.

During the height of the epidemic, the road the Johnsons live on—normally teeming with traffic—was eerily quiet, except for the constant fleet of emergency vehicles headed to the nearby crematorium.

“On a daily basis,” D.J. told AJWS, “you heard the sirens going up and down carrying loads and loads of bodies. Death was everywhere. People died on the streets.”

At least 4,716 people, to be exact, have died of Ebola in Liberia since March 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There have been more than 26,000 cases in West Africa overall. Liberia’s last known victim of Ebola died on March 27. Barring the discovery of a new case, Liberian officials are prepared to declare the country Ebola-free on May 9, after conducting a 42-day countdown.

AJWS on the ground

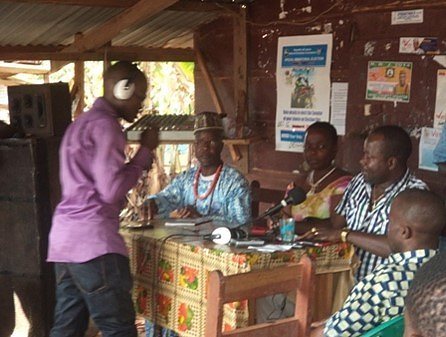

In two conference calls for AJWS supporters and interviews with AJWS, D.J. recently spoke about his work with AJWS grantees to stop the epidemic. He explained that 19 courageous organizations used AJWS funding to teach people in their communities how to implement the kinds of precautions that D.J. enforced on his family. Even as quarantine and travel bans restricted his work during the worst parts of the crisis, he continued to support grantees via phone and internet.

AJWS has worked in Liberia since 2003, and until Ebola hit, had provided more than $1.7 million in grants to advance human rights in the country.

When the Ebola crisis swelled last August, AJWS sent more than $763,000 in emergency aid to help its grantees lead public health campaigns; go door-to-door to educate communities about the virus; train religious leaders, women’s groups and media organizations to educate Liberians in their own languages; provide health care and psychosocial support to communities and work to stop stigma and discrimination against Ebola survivors; and collaborate with county health teams and task forces to ensure a coordinated response to the epidemic.

Overcoming the witchcraft myth

D.J. explained that Ebola spread rapidly in Liberia because many people didn’t take sufficient precautions. He says culture had a lot to do with that. “For Liberians, it’s difficult to greet you without shaking your hand,” D.J. said. “They will feel offended if you didn’t, especially elderly people.” The idea of quarantine is alien in this close-knit society.

Another deadly cause was mistrust and misinformation. The country’s civil war, which ended in 2003, left the population with an enduring mistrust of their government. For this reason, “A lot of people did not believe it [and] doubted it,” D.J. said of Ebola.

Many people thought news of the spreading disease was a cover-up for an impending invasion or civil war, a way for the government to embezzle money from the international community, or—because the devastation seemed so incomprehensible—witchcraft. Others saw the hazmat-clad international health workers as frightening foreign invaders.

As a result, many people eschewed health workers’ advice or took the sick to traditional healers, native doctors and spiritualists. And they didn’t heed instructions to stop the traditional practices of washing and dressing infected bodies before burial.

A trusted, grassroots response

In this climate of misinformation, mistrust and fear, D.J. says AJWS’s grantees were able to get messages through to people that outsiders could not. As trusted members of their communities, they went door-to-door and over the radio waves to convince people to take the life-saving precautions necessary to stop Ebola in its tracks.

The Bassa Women Development Association (BAWODA)—which before the epidemic worked to increase women’s participation in local human rights movements—ran Ebola protection trainings for women in communities throughout Grand Bassa County, a hard-hit area. The main takeaways: Ebola is not a government ploy, and it can be prevented by hand-washing, steering clear of dead bodies and refraining from eating wild animal meat.

BAWODA also deployed religious leaders as a powerful vehicle for educating large numbers of people.

“Their congregations believed them,” D.J. said. “They trusted them. This did a lot in preventing a lot of the infections.”

Not just hygiene

AJWS grantees also helped with the medical response to Ebola and the ramifications of the health system collapse it caused. Before the outbreak, Liberia had just 50 doctors and one health worker for every 3,400 people, D.J. said. Ebola killed about 180 of those workers.

“Thousands more people have died of other things, like childbirth or malaria,” D.J. continued. “I saw pregnant women, children and elderly people left to die in wheelbarrows in front of clinics or hospitals.”

Imani House International, an organization that offers clinics and housing for women and girls throughout the country, appealed to AJWS when the crisis began overburdening hospitals. Imani renovated a clinic to provide Ebola-related triage and routine health care to people in desperate need. When two Imani staff members caught the virus and tragically died, the surviving staff persevered with their work even as they mourned.

“The Ebola virus came so close to home, and they were still able to have the courage to open the clinic and serve communities,” Mr. Johnson marveled. “[Others would] just close the clinic, pack up and go.”

In Gbarnga, the capital of hard-hit Bong County, AJWS began funding Development Education Network-Liberia (DEN-L), which took on the task of locating sick people who were hiding throughout the county to evade quarantine, to prevent them from infecting others.

“The fact that such prevention measures were coming from within the community,” Mr. Johnson said, “rather than from the government or Westerners, made the people more trusting that these difficult things were necessary.”

Den-L also established teams of 15-20 youth to patrol communities at night, because ineffective policing during the height of the crisis led to a spate of burglaries and other crimes.

Looking ahead

All of AJWS’s grantees are still doing Ebola work, now focusing on message reinforcement to combat complacency and bring the number of cases down to zero, as well as providing psychosocial support to those who were left behind. Getting orphans back to school and destigmatizing survivors prove particularly challenging.

“It completely devastated these communities and traumatized people,” Mr. Johnson said. AJWS is currently formalizing a new grant to an organization that will train groups in counseling.

As the crisis slows, AJWS’s grantees in Liberia are working to fill in the gaps left by an exhausted health system and give relief to communities affected by food insecurity issues that Ebola caused.

“Most farms were abandoned, either because of migration or death due to the outbreak,” he said. “A major challenge will be getting the systems—governance, health, and accountability—working again. Civil society will have a major stake.”

D.J. says the past year has reminded him why he wanted to work for AJWS in the first place.

“This crisis has kind of underscored the important work that AJWS is doing in Liberia and the importance of AJWS’s approach of having community organizations take the lead,” he said. “A lot of [other] donor organizations set criteria that a lot of grantees could not meet. When [those organizations] leave, they only leave signboards behind to show they were in those communities. With AJWS, the impact lasts after they leave the community.”

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.