At AJWS, we talk about “collectives” a lot. About 40 percent of our grantees around the globe use collectives to advance human rights, and we invested $5.7 million in this work in 2018. In India alone—where AJWS has launched a multi-year, $30 million initiative to increase gender equality—our grantees support more than 3,500 collectives with 140,000 members.

The thing is…most people don’t know what collectives are.

It’s time to change that—because our grantees are using this powerful strategy to spark personal and political change around the world. Read on for a quick Q&A on how collectives work and why they’re so important to the communities AJWS supports.

What is collectivizing?

Collectivizing means regularly bringing together members of a group in ways that foster new friendships and opportunities for action. Members of collectives discuss the factors that have shaped their lives, identify shared challenges and brainstorm specific ways to address them.

Collectives supported by AJWS and other social justice organizations* aim to empower people who have faced oppression—for example, girls in India who face pressure to marry early, drop out of school and ignore any ambitions beyond cooking, cleaning and raising children.

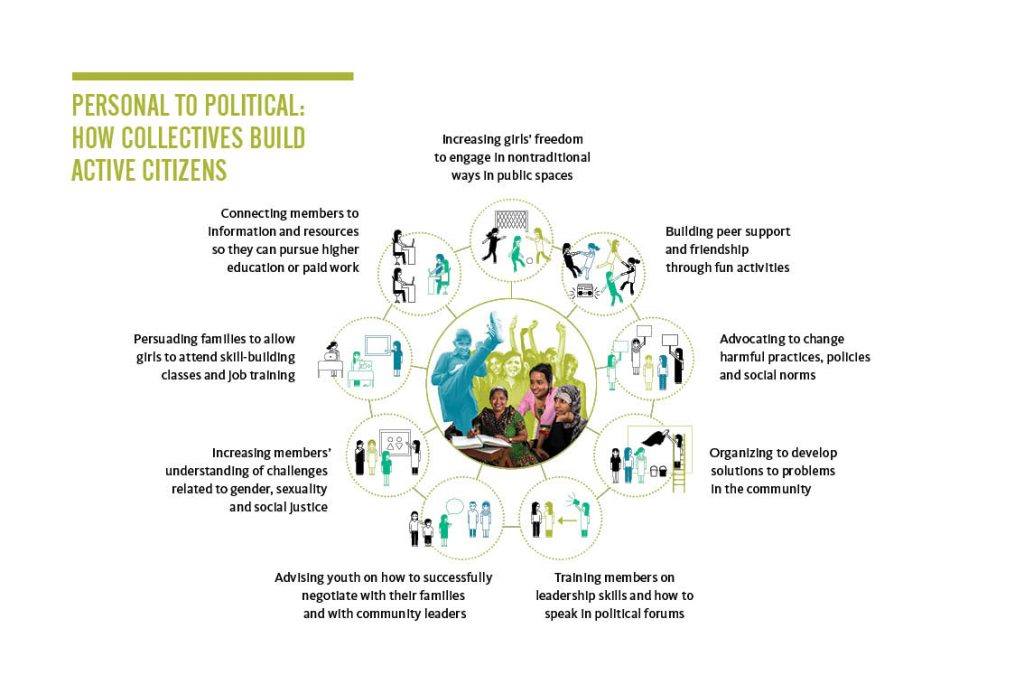

In collectives, members:

- Create safe spaces to seek emotional support and discuss their lives

- Learn about shared challenges related to their human rights

- Experience shifts in perspective and practice new skills and behaviors

- Develop their individual abilities to negotiate and to make decisions about their own lives and bodies

- Take political action together toward common goals for social change

How is collectivizing different from typical nonprofit programs?

While a lot of nonprofits offer programs designed to help participants in some way, the focus is often on getting large numbers of people to attend activities or classes for a limited period of time. It’s a popular approach because it’s so straight-forward and easy to measure. Experts can develop a curriculum or intervention, replicate it and reach very large numbers of people.

Unfortunately, those kinds of activities don’t always lead to big, lasting changes in people’s lives. Participants might gain new knowledge, but they might not develop the ability to think critically about the world, or they might not have the social support needed to apply what they’ve learned to their lives. It can be frustrating and lonely to be the only person speaking up about a problem that no one else wants to talk about—let alone trying to push forward a solution.

Collectives, on the other hand, encourage members to develop their own insights and goals within a caring group of peers. This approach eventually enables them to push for improvements—not just in their own lives, but in their communities. Clearly, this can be a much more complicated and time-consuming process than simply offering lessons. But it can also lead to far more meaningful and life changing results.

Exactly how does all of this add up to social change?

After participating in a collective for a while, members often start exercising greater power in their personal lives and supporting their peers to do the same. And in the process of sticking up for themselves, they begin influencing others in their family and community—inspiring those who have longed to speak out against the same harmful social norms, but were too afraid to act.

In India, for example, adolescent girls in collectives often start to negotiate with their parents, asking to delay arranged marriages and to pursue the same kinds of opportunities for work or education that boys get. This can lead to groundbreaking changes in communities where girls have traditionally been expected to do whatever their families ask.

Over time, collective members build the skills and shared momentum they need to do something about the challenges they’re facing, rather than waiting for some outside organization or politician to step in and make decisions for them. Some collectives launch campaigns in their communities to demand new laws, policies or services. For example, some collectives push for more affordable housing, try to halt projects that threaten to devastate the environment or use social pressure to convince controlling parents to let their daughters attend after-school activities.

This kind of political initiative is no small feat for collective members, who often grow up under the impression that they possess little or no power. It’s also an effective way to make better decisions for communities, because the people directly affected by a problem often possess deep insight into how to solve it.

I/my mom/my friend joined a collective in the ‘70s. Is this basically the same thing?

It’s probably similar. Some people call this kind of work collectivizing; some people call it community organizing. If you ever read philosopher Paulo Freire’s work on “conscientização,” you’ll recognize his influence on collectivizing, too.

While academics and activists might use different terms—and the details of their definitions and theories might vary—they’re usually talking about efforts to increase the power of people who have historically not had much.

To learn more, check out AJWS’s latest data story on collectivizing girls in India or read a blog post on this topic from AJWS consultant Rama Vedula.

*It’s worth noting that collectivizing isn’t exclusively used to advance progressive causes. Some political groups use similar strategies to promote conservative causes.

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.