Ruth Messinger’s dedication to social justice runs deep.

“I feel like I’ve been an activist my whole life,” she said. “I was raised to care about social justice and to believe that problems existed, that change was possible and that we all had to do our part to help heal the world. My parents suggested that it was a fundamental Jewish obligation—and our main purpose for being on this earth.”

Ruth Messinger’s commitment to this obligation propelled her life’s work—from her early years as a social worker, to two decades in New York City public service, to her legendary 18 years at the helm of American Jewish World Service. Under her leadership, AJWS has granted more than $300 million to more than 1,000 grassroots organizations in dozens of developing countries and has launched campaigns to end the Darfur genocide, reform international food aid, stop violence against women, respond to natural disasters worldwide and defend land rights for indigenous farmers.

A tireless and visionary advocate for social change, Ruth mobilizes American Jews and others to speak out about injustice, give generously, and advocate for poor, oppressed and persecuted communities around the globe.

The Making of an Activist

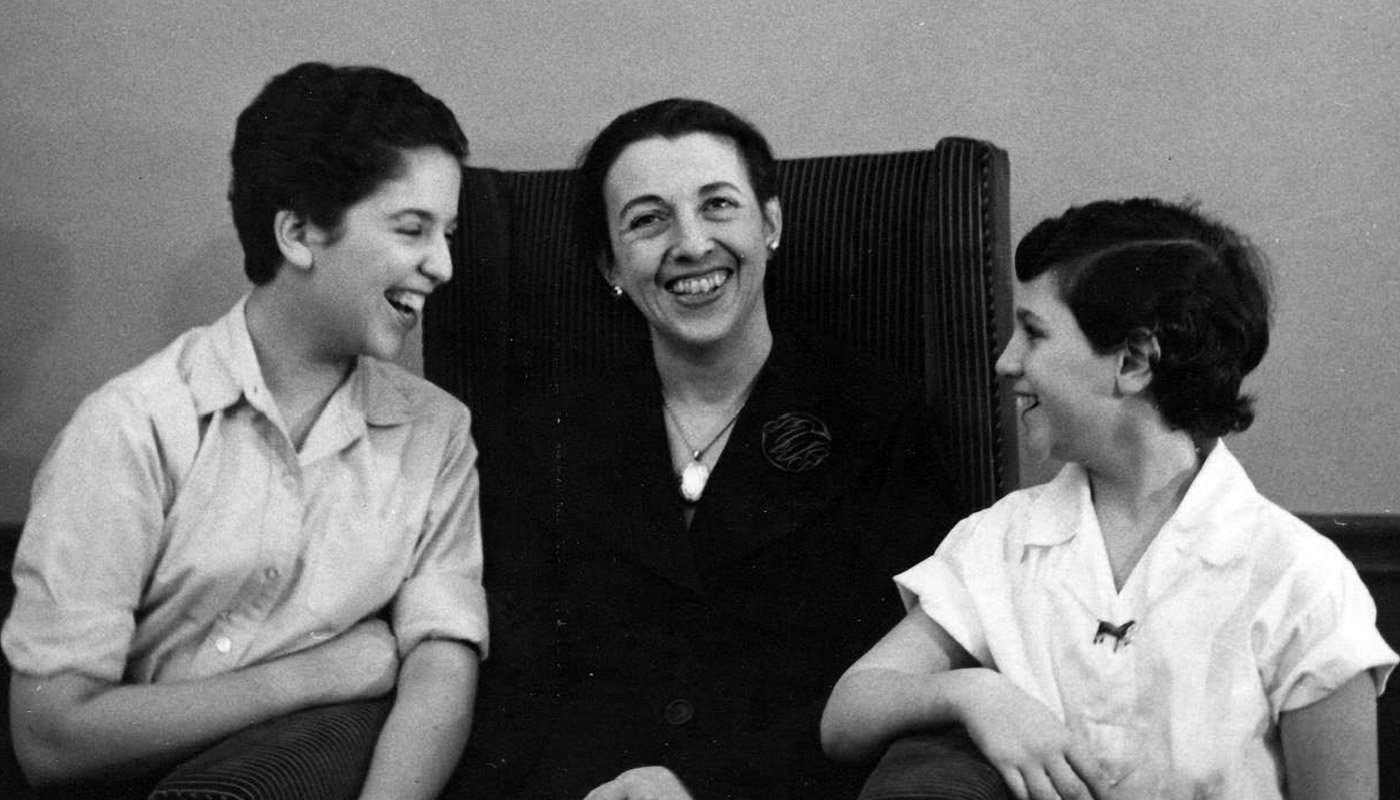

Born Ruth Wyler in 1940 in New York City, Ruth was deeply influenced by her family and her surroundings. Living on Manhattan’s Upper West Side— at the time a middle-class neighborhood—her parents taught their children liberal democratic values and fostered in Ruth an early concern for national and international issues.

Her mother, the late Marjorie G. Wyler, served for five decades as the Public Relations Director of the Jewish Theological Seminary—promoting Conservative Judaism and working alongside luminaries like Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, whom she joined on the historic 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery.

“My parents nurtured in me a sense of a responsibility to give something back; to be good to the country that had been good to our family; to be good to the city that had been good to our family; and to be good to the Jewish community,” Ruth said.

By her early teens, she had distinguished herself at Manhattan’s prestigious Brearley School as an intellectual and politically active young person. She wore buttons for social justice causes, passed out literature and attended rallies to show support for Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson’s two presidential runs against Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956.

At 15, Ruth worked at a camp for Lower East Side children run by the University Settlement House and subsequently volunteered at the settlement house. And at 17, she got involved in anti-war work around the city—joining other young people who sought to stem early U.S. military engagement in Southeast Asia as tensions rose prior to the Vietnam War.

“I was passionate about stopping the spread of war and loved being a part of the movement,” she said. “It eventually led me to take part in more anti-war work and in the civil rights movement supporting Dr. King and working with organizations that were exposing issues of racism in New York City. My life’s work has been, in many ways, an extension of this early activism.”

An Education in Equality, Compassion and the Importance of Helping Others

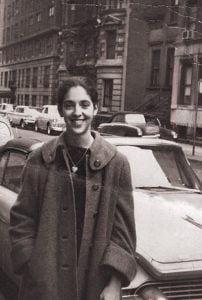

After graduating from Brearley, whose yearbook dubbed Ruth “Class Brain,” she went to Radcliffe College, the women’s undergraduate school within Harvard University. While studying government, she began to promote issues of gender equality—born partly from her acute awareness of the “strange restrictions” on Radcliffe students in Harvard’s male-centric culture.

“All of our classes were entirely integrated with Harvard’s,” she recalled, “but our dormitories were nearly a mile away. We commuted on foot and by bike, but could only wear pants if it was snowing. And there was one Harvard library that women weren’t allowed into. We accepted all of these rules, which is astounding when I think about it, but it never sat well with me.”

Ruth served on an advisory board of students convened by Radcliffe’s president to propose ways to enhance the quality of social and academic life for women at Harvard. She also found several hours a week to volunteer at a psychiatric hospital, increasing her growing interest in social work.

“[Ruth] was the first person I ever met whose life was so organized she had lists,” her Radcliffe roommate, Sharon Levisohn, told The New York Times in 1997 during Ruth’s bid for mayor of New York City.

One summer, Ruth interned at Jewish Family Services (JFS), a New York City agency that served many communities, including the South Bronx. Ruth managed a playroom for mothers with counseling appointments, and remembers the women’s tremendous gratitude for this resource provided by the Jewish community. “JFS taught poor families in the South Bronx that Jewish people care about them,” she recalled.

This experience showed Ruth that “the way we act in the world, as Jews, informs the way the world sees us”—a lesson that later inspired her at American Jewish World Service. “Today, AJWS lets people in Cambodia and Guatemala discover that there are Jews in the world, and that an organization run by Jews helps them with full respect for them and their values.”

Shifts in Geography and Perspective

When she graduated from Radcliffe in 1962, Ruth pursued a master’s in social work from Columbia University and did field work in the South Bronx. She married a young physician—her first husband, Eli Messinger—and in 1963 moved with him to Oklahoma after he joined the federal Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. This move, to a place socially and culturally unlike all she had known, changed Ruth’s perspective on society, further deepened her connection to her Jewish identity, and eventually turned her toward a career in community organizing, public service and politics.

She completed her M.S.W. at the University of Oklahoma, where all but one of her fellow students were the first generation in their family to attend college. And it was in her small, rural, economically-depressed town that she heard others express openly anti-Semitic opinions for the first time, providing her first sense of “otherness.”

“We were the only Jews most people we met had ever encountered,” she said. “I remember one couple where we lived in Oklahoma describing the sign at the edge of their town in Indiana: ‘No Jews or Negroes after sundown.’ My early weeks in Oklahoma were quite instructive.”

Feeling different deepened Ruth’s engagement with her Jewish identity and the meaning of Judaism. “I had never anticipated what it would mean to live in a community with no other Jews,” she said. “I was, to my surprise, suddenly taken with the internal force of my Judaism. I drove 35 miles to a Friday night service during our first summer to see if there really was a place to go for the holidays. I was constantly trying to define in my head, what do I think about Judaism, how important is it to me, and how do I respond to the anti-Semitic remarks that are part of people’s casual conversation.”

During this time, Ruth was recruited by the local Democratic Party, where she campaigned aggressively for its candidates: Lyndon Johnson, for president; and Fred Harris, a progressive populist, who won his U.S. Senate seat and served for nine years. She played an important role in helping both candidates win in the Republican districts she worked in.

Stepping Into Leadership

The summer before completing her degree, Ruth interned at the state’s Child Welfare Department—an experience that soon led to her first job. Just before graduation, the agency called to ask her to run the departments of child welfare for two counties in Western Oklahoma—a surprising prospect for a newly-minted social worker. The reason? Ruth was the only person who qualified: “The federal Child Welfare Reform Act required that county departments of child welfare be run by someone who held a master’s in social work, and I was the only M.S.W. in the area!”

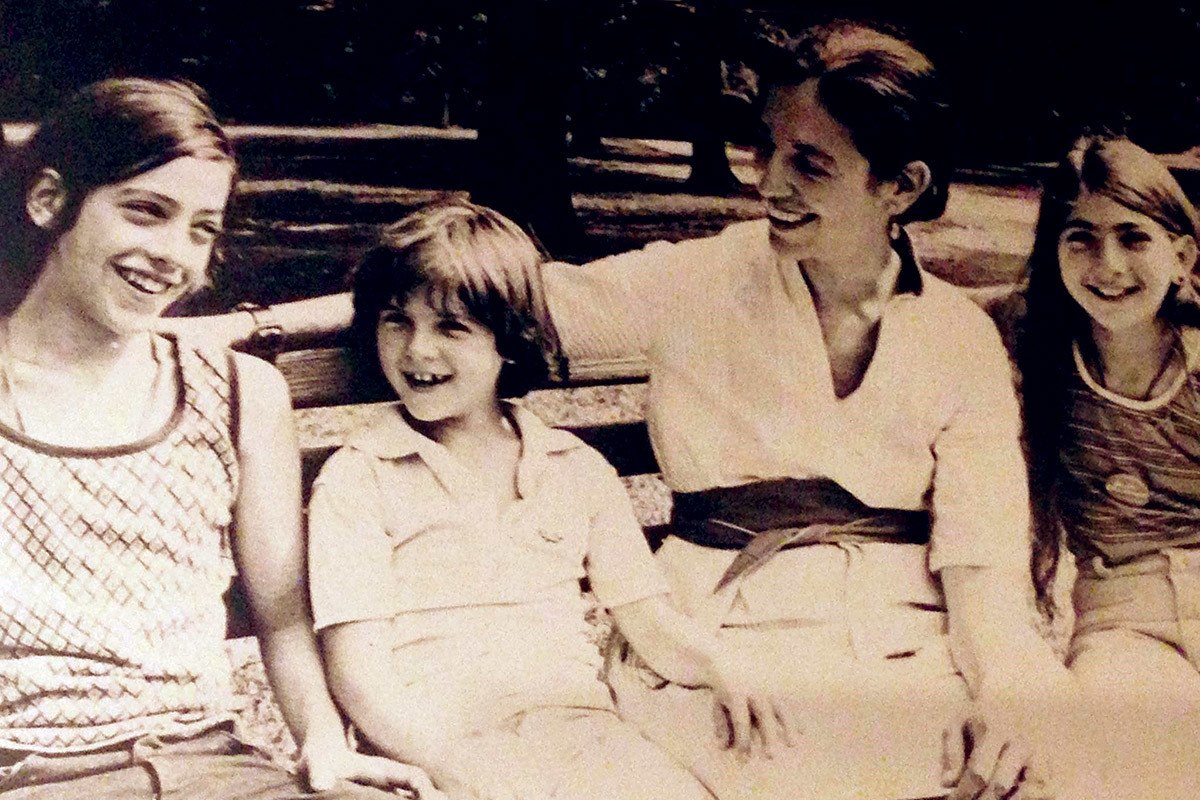

Ruth initially demurred, as the role was daunting and she was pregnant with Daniel, her first of three children. But after the agency called Washington to secure a waiver so she could work part-time, she agreed. That year, she taught herself to manage an organization, find common ground with people of different backgrounds, and change the way things were done within a system strongly wed to the status quo—all vital skills that would later serve her well in both government and human rights work.

“You know how people say, ‘everything I need to know I learned in kindergarten?’ I would say the same about that job.”

It was truly an education in grit and perseverance.

“At one point,” she said, “I had to convince a county attorney, a county judge and a county sheriff to change virtually everything they did with regard to the treatment of minors. These three men were disparaging of women, only knew their own town and didn’t like outsiders. And here I was—a young Jewish woman from New York City with a title and a position with authority over them. They weren’t happy about it, and they surely didn’t like how fast I talked, but I had the law on my side, and I controlled federal funds. This was a great organizing and social change opportunity, because we all knew that they didn’t want to make change, but that I was going to make them do it anyway.”

Ruth was pregnant with Miriam, her second child, in 1965 when she and Eli returned to New York to live in the Northeast Bronx. For several years, she continued her social work career, doing case work with families and participating in a major social welfare research study. In her spare time, she volunteered building the anti-war movement in the South Bronx, adeptly setting up a service for counseling young, poor men of color who wanted to resist the draft. Ruth was also active in Women Strike for Peace, the iconic anti-war organization that first protested nuclear proliferation and, later, the war in Vietnam.

In 1966, she joined a movement to fight racism in New York City. Subsequently, in 1968, she and a group of parents helped launch the Children’s Community Workshop School, a foundation-supported school that would provide racially and economically diverse education on Manhattan’s West Side.

“This work used all of my skills,” she recalled. “It gave me a chance to get to know a different part of the West Side community. I saw the neighborhood where I had grown up in all its diversity and had a chance to work with parents from a full range of backgrounds who were trying to figure out how to improve their kids’ education and were committed to advocating for and negotiating with the government to support their ambitious goals.”

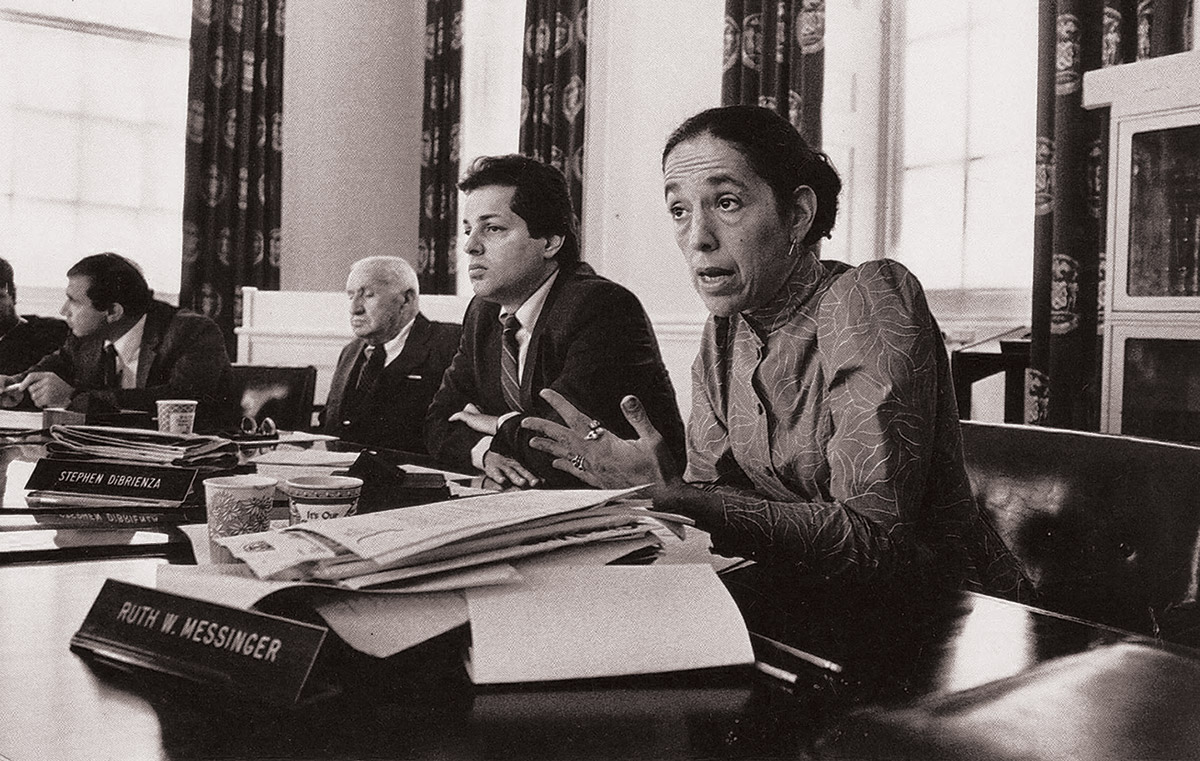

From Local Leader to Elected Official

While Ruth helped build the school that her children attended, she got involved with West Side community groups that were fighting for issues like affordable day care and housing, and challenging the city’s efforts to oust poor people in order to gentrify the neighborhood. Ruth soon established herself in the community as a capable and trustworthy leader.

In 1974, local parents asked her to consider running for the school board. Although she was then juggling a new job at a college for low-income adults as well as childrearing—her third child, Adam, was born in 1968—she saw board service as an opportunity to shape public policy. She won her seat and served from 1975 until 1977—a time “full of excitement and political challenges and lots of opportunities to organize,” she said. “We disagreed with the Central Board of Education, and we fought them on many different occasions. I learned a lot about organizing for change.”

The position also made Ruth something of a household name on the Upper West Side. “Our school board was making a lot of trouble and I was one of the lead troublemakers,” she said. “I was a powerful force in demonstrating to people that you can make change; that you can organize and fight for what you believe in. You don’t get everything you started out looking for, but you get something.”

The board appointed her as a liaison to legislators, a post that gave her an insider’s view of the political process—which both frustrated and emboldened her to believe that she could do more on behalf of New York City’s less well-off people than those currently in power.

In 1976, Ruth threw her hat in the ring of city politics by running for State Assembly. As a newcomer, she surprised many established local politicians with her popularity, but lost the election by a hair.

Exhilarated but practical, she was ready to “go back to everything else I was doing in my life,” but her supporters insisted that she persevere. “You just ran this astounding campaign,” she recalled them telling her. “‘You’re absolutely obligated to keep running until you win a seat.’ I don’t know what would have happened if people hadn’t said that to me. That was another turning point.”

One year later, in 1977, she ran for City Council—and won. During the 12 years she represented the West Side, she became known for giving a voice to community groups in her district who were seeking social change, and for finding ways to move city money to local youth groups, child welfare, human service and public education programs.

In the council, she got involved in and eventually led the charge to pass New York City’s first anti-discrimination bill to protect the rights of gays and lesbians in housing, employment and public services. To pass the bill, she helped overcome opposition by a powerful coalition backed by the Roman Catholic Church, some Orthodox Jews, and conservative religious leaders. She also became a prominent advocate for HIV-positive New Yorkers at the height of the AIDS crisis in the early ‘80s.

An article in The New York Times looking back at this period said of her: “Her colleagues—friends and foes alike—said that through the force of her intellect, the thoroughness of her research and her awesome work habits, she became one of the most respected and best-known members of the Council in the ‘80s. Ruth garnered favor and influence by mastering complicated issues and then educating everyone around her.”

Attaining Higher Office

In 1989, Ruth was elected Manhattan Borough President. She served for eight years, earning admiration for continuing to champion social justice causes and make waves on budgets, tax policy, child welfare, housing and urban development issues.

She worked with colleagues to improve accountability in the schools and move more funds to the local level so that the community could have a say in how children are educated. She helped fund critical but neglected cultural and neighborhood institutions—allotting, for example, $1.8 million to remove asbestos and clean the plumbing at the American Museum of Natural History. She helped thousands of constituents get potholes filled and sidewalks fixed. She was a pioneer in encouraging local communities to design their own zoning and redevelopment programs. She was also very involved in limiting city tax abatement programs that were overly generous to developers.

The media in the late ‘90s marveled at Ruth’s work ethic and determination. In The New York Times, journalist Frank Bruni said she “succeeded in defining and distilling her political identity as a champion of underdogs more dogged than most others, a true believer in the aggressive ministrations of government and a populist ready to challenge the corporate interests that other politicians were more reluctant to estrange. … Ruth has always made it a point to care, even when she was one of the only ones.”

A New York magazine journalist wrote, “All major politicians keep long hours, but her schedule verges on punishing. She probably knows more about the city budget than the last three budget directors combined. She is constantly showing up … clutching vast sheaves of papers, and even when she sits, it’s to work some more: While everyone else is giving attention to [the Schools’ chancellor], there sits Ruth, scribbling on her note pad, reading memos, writing reminders, but listening closely enough with one ear to smile to herself when [the chancellor] says something she suspects won’t sit too well with [the teachers’ union chief]. … She’s a terrific public servant.”

Ruth says simply that she “loved local government,” where she learned “how to challenge the powers that be, put forward significant proposals for change, and recognize that progress comes slowly.”

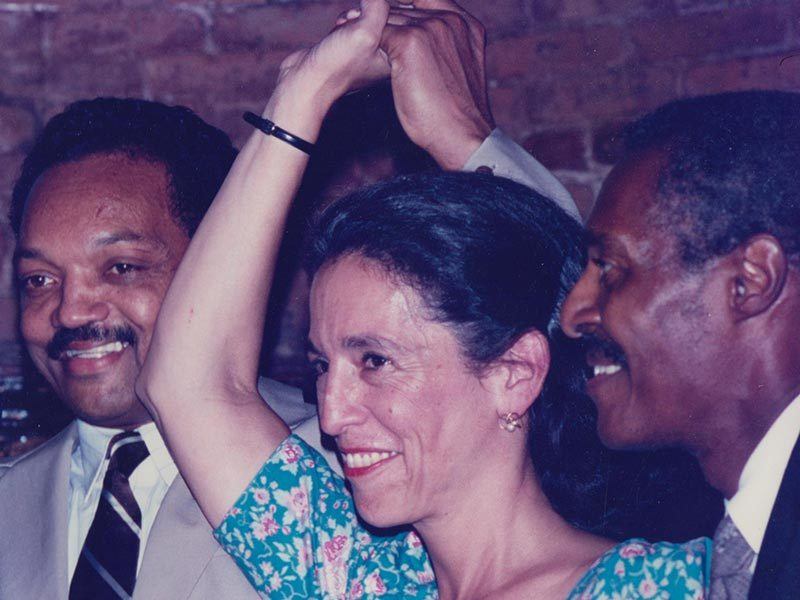

As Borough President, Ruth was one of just a few white politicians to stand firmly with Mayor David Dinkins—the first and (as of this writing in 2016) only black mayor of New York City—whose tenure from 1990 to 1994 was marked by significant racial animosity in the city, particularly in parts of the outer boroughs. Ruth’s commitment to equality for African Americans made her a strong ally of Mayor Dinkins, who was often a target of attack.

A Historic Bid For Mayor

In 1997, she launched a bid for mayor herself, boldly confronting popular incumbent Rudolph Giuliani and winning a primary against the Rev. Al Sharpton, an influential civil rights leader, and Fernando “Freddy” Ferrer, the Bronx Borough President, to become the first woman ever to receive the Democratic nomination in New York City.

Although Ruth was considered the underdog, she was an icon in her borough and ran a campaign driven by her hallmark passion for social justice and community engagement. With strong momentum for her campaign mounting, “Some people thought we might be able to pull off an upset,” she said.

She had powerful allies on her side—most notably President Bill Clinton, Ted Kennedy, Al Gore and other leaders of the Democratic Party.

Despite strong support from her constituents in Manhattan, Ruth lost her bid for mayor. But the closing of this chapter soon led to the opening of another. Within the year, Ruth began a deep new engagement with global issues and assumed a new form of leadership for social change at American Jewish World Service.

Taking the Lead at American Jewish World Service

In 1998, after she had begun teaching and consulting, Ruth was contacted by Martin Horwitz, the director of the Jewish Community Development Fund in Russia and Ukraine. Horwitz’s organization operated out of the offices of American Jewish World Service—an international development and humanitarian organization founded in 1985 that had made a name for itself by supporting community-based responses to poverty and disasters in developing countries.

Thirteen years into its history, AJWS, like Ruth, was at a crossroads—searching for a new president to replace its outgoing leader, Andrew Griffel. Horwitz consulted with his wife, Madeline Lee, head of the New York Foundation, who thought Ruth would be an unorthodox—but stellar—choice.

Although Ruth had never worked in the field of international development and the organization was unfamiliar to her, she was intrigued. In August of 1998, she took on the job, inheriting a staff of 13 people and a budget of $2.4 million. She soon launched AJWS on a trajectory of dramatic growth: In less than two decades, she came to lead a staff of 130 with a $38 million budget working to promote human rights around the world.

Learning on the Job

Ruth’s first task as AJWS’s president was to give herself a rapid education in international development and the human rights challenges the organization was tackling. Conversations with staff and visits to AJWS’s grantees taught her that investing in local organizations was the key to creating sustainable solutions to poverty and injustice.

“Very quickly, I came to love the notion that AJWS supports smaller grassroots and community-based organizations and lets them set their own agendas,” she said. “I was inspired by how much change it was possible for these individuals and their communities to make, how many people were fighting to improve their own situations, how many of these people really had started their work when they had no funding. They were doing it because they believed it was time for a change, taking on fights and battles for human rights.”

Ruth quickly learned the importance of listening to these leaders: “They know best what their communities need, and AJWS listens to those needs before we respond. That resonated with me and was very connected to the work I had done in city government.”

During an early trip to Zimbabwe, Ruth saw this approach in action. She learned from a local school teacher that the greatest barrier to educating the local children wasn’t a lack of books or classrooms; it was the pervasive hunger that distracted them from learning.

During her early trips, Ruth also began to savor the way AJWS’s work was spreading the message that there are Jews in the world who support the aspirations of people of all backgrounds. On her very first trip, to El Salvador, she visited a small grassroots group called La Coordinadora del Bajo Lempa, which helped indigenous people conserve their land and overcome poverty. The group greeted the AJWS contingent with a sign welcoming ‘the American Jewish community.’ “That was wonderful,” Ruth said. “We were hardly the American Jewish community, but to this group of Salvadoran activists, we were, and we shaped their understanding of who Jews are in the world.”

Indeed, AJWS’s Jewish identity spoke to Ruth. “This model of Judaism—the idea that Jews are responsible for building a better world—was the type of Judaism I was raised with. This was a chance for me to be in Jewish circles and say, ‘Here’s something new, different and important that Jews are doing and should be doing more of in the world.’”

On The Frontlines of Disasters

Ruth’s early years at AJWS coincided with an intense period of frequent world disasters, and she took steps to ensure that AJWS responded nimbly.

“Disasters snap people’s attention to parts of the world that are typically not on their radar,” she told her staff. “We’re going to use our unique approach to local, grassroots development to provide emergency aid and build local aid efforts, and that’s how we’re going to make a much larger difference in the world and get our name out in the Jewish community.”

Under Ruth’s direction, AJWS responded to Hurricane Mitch, which devastated large swaths of Central America in 1998; aided survivors of earthquakes in El Salvador and Turkey; and aided victims of fierce ethnic cleansing in Kosovo.

In 2004, AJWS took its disaster expertise to the next level when a massive tsunami struck the coast of Southeast Asia. “Our response showed our capacity to very nimbly and thoughtfully respond to a large-scale disaster,” Ruth said. “I believe it truly set the model for how we work in emergencies. Most international aid groups focused on relief, but we were doing relief plus development and human rights work. We didn’t run in with food and blankets. We made it possible for our local grantees, the people who know these places best, to provide what survivors needed and to help people change their circumstances.”

AJWS became a long-term presence in communities that lost everything in the tsunami—granting nearly $11 million in disaster aid to 82 grassroots organizations in five countries over several years. According to Ruth, “when AJWS responds to disasters, we stay for the long haul so people can recover, change their circumstances and realize their rights.”

Leading the Jewish Response to Darfur

Earlier that same year, news of the Darfur genocide broke—and AJWS’s response “put us dramatically on the map in a way we hadn’t been before,” Ruth said. Thanks to the visibility raised by Ruth and her team, Jews around the United States chose AJWS as their vehicle to respond.

With more than $5 million contributed during the years the genocide raged, AJWS funded grantees in Darfur and Chad working to save lives and end the atrocities.

Ruth was determined to respond as soon as she learned of the horrors happening in Darfur. She told AJWS’s staff and board: “Our own people have suffered what the Darfuri people are now suffering. We were raised to promise ‘never again,’ and this is our chance to act on that promise.”

AJWS soon launched a massive advocacy campaign uniting Jewish organizations and other faith-based groups across the U.S. behind the cause. In the summer of 2004, right after Congress and the White House declared the crisis a “genocide,” AJWS convened a meeting to call other Jewish organizations to action—enlisting Elie Wiesel to speak. “So many groups came, including many outside the Jewish community, that the fire marshal threatened to shut the first meeting down,” Ruth recalled.

AJWS and other participants in the meeting founded the Save Darfur Coalition to respond to the genocide. Ruth served on its board and became one of its leading voices, helping bring the genocide into the spotlight in the Jewish community and on the global stage.

In recognition of AJWS’s role in responding to the genocide in Darfur, Pulitzer-winning journalist Nicholas Kristof, a columnist for The New York Times, said in 2012: “There are hundreds of thousands of people who are alive today in camps in Darfur who would not be alive if Ruth and the people she works with had not led that quite extraordinary campaign. She was one of the first people to really appreciate that this was a genocide and that it was very important for the Jewish community—and for everybody—to address what was going on.”

In 2009, Ruth was called on, with other leaders of the Darfur movement, to advise President Obama on human rights strategies and peace-building efforts to shape Darfur’s future. She later advised Obama’s Special Envoy for Sudan, General J. Scott Gration, and joined a delegation of international leaders convened by Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, to participate in the second Sudanese Women’s Forum on Darfur (SWOFOD) in Addis Ababa to strengthen the role of Sudanese women in the peacemaking process and to deepen relationships between the African and global women’s movements.

To this day, Ruth continues to collaborate with faith-based, humanitarian and advocacy organizations to bring an end to the conflict that still plagues the region. She has also met with President Obama and with Samantha Power—now the U.S. Ambassador to the UN—about the continuing violence and the challenges of creating a sustainable path toward peace.

Ruth is still devastated by the number of lives lost and continues to advocate for those who suffer from the ongoing brutality in the region. “That’s why I still have my Darfur bracelet on,” she said in 2016.

Raising AJWS’s Profile and Capacity to Succeed

With Ruth leading the way, AJWS has become a powerful advocate for human rights in Washington. Early in her tenure, it opened an advocacy office to lobby Congress and the White House. Today, AJWS is sought out to lead and join coalitions and collaborate with policymakers to draft and advance legislation on key issues—including curbing HIV/AIDS, reducing global hunger, securing debt relief for struggling nations, stopping violence against women and LGBTQI+ people, and helping indigenous farmers hold on to their land.

Ruth and her team have mobilized American Jews to add their voices to many of these campaigns, and she takes great pride in “the capacity that we’ve demonstrated to mobilize people very quickly and to achieve results.”

In 2014, after collecting thousands of signatures and sending supporters to lobby Congress, AJWS and its allies helped secure a new program in the U.S. Farm Bill that provides up to $400 million in funding to buy food aid from local farmers in the developing world. The program enables life-sustaining food assistance to reach more people faster while also supporting local farmers, who are the key to creating long-term food security for vulnerable communities and countries. And in 2015, AJWS led the advocacy effort resulting in the appointment of the State Department’s first Special Envoy for the Human Rights of LGBTQI+ Persons, who will strive to ensure that U.S. foreign policy protects and defends the dignity and security of LGBTQI+ people worldwide.

“On these issues and others,” Ruth said, “our Washington staff is viewed by members of Congress and the Obama administration as valuable partners in pushing policy change through our government.”

Ruth, herself, has spoken around the world to represent AJWS and amplify its message. She has represented AJWS in a variety of world forums, including the Clinton Global Initiative, the International AIDS Conference, Women Deliver Global Conference, Nexus Global Youth Summit and Global Philanthropy Forum. She served on the Obama administration’s Task Force on Global Poverty and Development and currently serves on the State Department’s Religion and Foreign Policy Working Group. In 2015, she was invited to represent the American Jewish community on a faith-based taskforce put together by the World Bank Group to argue for a moral imperative to end extreme poverty by 2030.

“People see us as the Jewish voice for global justice,” Ruth said.

Orchestrating Growth and Sustainable Change

Ruth’s greatest challenge—and accomplishment—at AJWS has been to steer the organization through a meteoric rise and manage its growth in a sustainable way. In recent years, she and Robert Bank, whom she brought on in 2009 as AJWS’s first Executive Vice President, led the organization through a rigorous process of board development and strategic planning. The plan, adopted in 2011, focused and deepened AJWS’s work, aligned its international grantmaking with its domestic advocacy, and reinforced AJWS’s ability to measure and communicate its impact.

Through all of this change, Ruth has led AJWS in a very hands-on way. “I’ve loved watching AJWS grow, but it’s also a constant adjustment—how you act when you have a staff of 13 to how you act when you have a staff of more than 100. I think I may occasionally be too hands-on, but it’s the way I like to be. I want to know what’s going on, I want to be there, I want people to know that I care about the small things in people’s work and lives.”

Transition to a New Era of Leadership

A major testament to Ruth’s dedication to AJWS’s future is the fact that the board of trustees chose Robert—who had led the organization by her side for the previous seven years—as the next president of AJWS. When Robert became president on July 1st, 2016, Ruth assumed the new role of Global Ambassador, continuing her crucial work of engaging rabbis and interfaith leaders in efforts to end poverty and promote human rights in the developing world.

“I am humbled to follow in Ruth’s footsteps and am committed to building on her extraordinary legacy,” Robert said. “Like Ruth, I am motivated by a deeply felt devotion as a Jew to fight for the basic human dignity of every person.”

When the transition plan was announced, AJWS Board Chair Kathleen Levin said: “Ruth’s contributions to AJWS and her unwavering dedication, passion and leadership cannot be overstated. She leaves a legacy of accomplishments for human rights and dignity around the world.”

For Ruth, this transition marks a new era: “For nearly 20 years, AJWS has afforded me the opportunity to live my values and to work every day to stand up as a Jewish leader for some of the most vulnerable and oppressed communities in the world,” she said. “Serving as president of AJWS could not have been more rewarding, and I look forward to continuing to serve AJWS as its Global Ambassador. I am deeply gratified that our board chose the incredibly competent, strategic and passionate Robert Bank to take the helm at AJWS. Robert will provide the vision and leadership the organization needs for years to come.”

Translating Values into Action

Ruth has always put her values into action—particularly those derived from her Jewish heritage and from the principles of equality enshrined in the U.S. Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. From her early activism to her years in local government to her leadership at AJWS, the same principles have served as her compass.

She has always been moved by a quote from the late Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, an influential philosopher, whom she knew and still considers a teacher and mentor: “In a free society, where terrible wrongs exist, some are guilty, but all are responsible.”

“Heschel’s quote speaks about the same ethic that motivated the work I did in the ‘60s, and that motivates me at AJWS today,” she said. “I didn’t cause urban racism or bad schools, I didn’t cause land theft in Guatemala. But I’m still responsible for it. In some cases, the problems that exist in the world were created by the U.S. government; and in other cases, we are responsible purely because we are human and we are citizens of this world. Either way, as a Jew, I have to act, I have to assume responsibility for things that aren’t the way they ought to be, and I have to work to create greater justice. I’d like to think I did that as a young activist—and I know I do it today.”

Acting on these values, Ruth has helped more American Jews view tikkun olam—the Jewish responsibility to repair the world—as a central guiding principle of Jewish life in the 21st century. Recognizing Ruth’s influence, dozens of national Jewish organizations have honored her, and she has received honorary degrees from five major American rabbinical seminaries. She was named to The Jewish Daily Forward’s “Forward 50” for nine years and was sixth in The Jerusalem Post’s list of the world’s 50 most influential Jews in 2012. The Huffington Post included her as one of the “10 most inspiring women religious leaders of 2012.”

Ruth has passed on this passion to act on her values to the next generation. Her granddaughter, Chana Messinger, reflected: “Belonging to a family that treats activism as not necessarily an activity or an extracurricular hobby, but as a genuine part of what it means to be a human, in this day and age, is really beautiful.” Beyond her family, countless activists consider Ruth their inspiration in this regard, and they now live and act on the ethos she taught them.

“A Force of Nature”

Many people call Ruth, now 76, “a force of nature.”

She is known for getting by on very little sleep and jumping time zones with ease. As AJWS President, she spent about six months a year travelling around the country and the world—usually carrying little more than a backpack and a camera. She also multi-tasks with boundless energy and focus: It is not unusual to find her participating actively in a meeting while reviewing documents and completing The New York Times crossword puzzle or working on a Sudoku puzzle. Ruth’s staff joke that all this activity is fueled by her drink of choice, Diet Coke.

When Ruth is not at AJWS or traveling, she lectures widely on social and global justice issues and actively participates in her congregation, the Society for the Advancement of Judaism, on the Upper West Side. She serves on the boards of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy, Hazon, United to End Genocide, Interaction and Surprise Lake Camp.

Ruth remains active in Democratic Party politics—hosting fundraisers for candidates in her home, advising city officials who solicit her advice and commenting frequently for journalists who cover New York City politics and government.

She is married to Andrew Lachman, who runs a nonprofit organization focused on public education in Connecticut. They support each other’s work, delight in their shared hobbies and manage to find time with each other, even when it isn’t easy. Ruth has three adult children—who survived the rigors of growing up with a mother who was an activist and public official—as well as eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. She is proud of their individual and family accomplishments and continues to learn from them.

When asked what keeps her going despite all of the injustice she sees in the world, she said: “I’m an optimist, in general. There are times when I get as upset or depressed as anyone else. I am human. But, in general, I consider myself very privileged for all the things I’ve been able to do, and I love the work. I approach the world with an optimistic lens, even when it looks as if things are pretty terrible.”

Rabbi Joy Levitt, executive director of JCC Manhattan and one of Ruth’s close friends, called her “tireless,” because she is “constantly balancing her anger at the way the world works and her indomitable optimism at our ability to make things better.” As a result, “she has made us better.”

“No one wears her dedication, enthusiasm or relentless commitments better than Ruth does, and no one shares all of that with more generosity than Ruth does. She has demonstrated that it is possible to lead, to grow an organization in astonishing ways and to always bring freshly baked cookies to Shabbat dinner, while at the same time telling the truth, making hard choices and not cutting corners.”

In another tribute, The Forward once said that she “simply never gives up.”

“That is true,” Messenger confirmed. “The causes we pursue at AJWS—fighting hunger and poverty, ending genocide, empowering women, stopping land grabbing and advancing justice—are too important to our civilization’s future for us to retreat to the convenience of being overwhelmed.”