Around the world, selling sex is as inflammatory an issue as abortion. It’s just as divisive, too—particularly among feminists and in the global human rights community.

Around the world, selling sex is as inflammatory an issue as abortion. It’s just as divisive, too—particularly among feminists and in the global human rights community.

At the 2012 AWID Forum—the largest women’s rights gathering in the world—sex workers’ rights took center stage. Panel discussions and plenary sessions featured sex workers from Burma, Thailand and Cambodia, along with myriad organizations—including several AJWS grantees—that protect sex workers from human rights violations. One grantee offered a clever metaphor to capture how sex work is relatively alien to women’s rights conversations. “Imagine you go to a restaurant with a friend,” she said. “You order beef. But your friend explains she is vegetarian, so she orders a plate of rice and vegetables. You look at her plate and think to yourself, ‘This is a bit strange; a little different.’ But it’s a choice on the menu. And it’s a choice she made herself, just like any other choice. That’s sex work—a choice.”

People who are engaged in the sex work debate generally fall into two camps: 1) Those who understand sex work as a labor rights issue and want to decriminalize prostitution; 2) Those who view selling sex as an exploitative trap and, therefore, call for intensified criminalization and government sanctions. Ultimately, the debate is animated by two core questions: How much choice, agency and consent do sex workers have in their lives and in their work? How do policymakers and activists respond to actual or perceived violence?

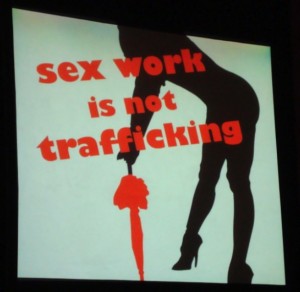

Questions aside, I’m struck by how loaded the language is in this debate. Sex slavery, sex trafficking, sex trade, sex work, sexual commerce—there’s a lot to unpack. It’s similar to the feminist debate about pornography in which “abolitionist feminists” often describe pornography as “rape on paper”—a sensationalized charge that sometimes reflects reality and sometimes doesn’t.

I’m also struck by how sex trafficking is increasingly conflated with sex work. Clearly, the issues are different: Sex trafficking refers to forced migration of human beings—often minors—for sexual exploitation and coercive labor. Sex work refers to people—women, men and transgender individuals—who sell sex to earn a living. Sex work is work and, more often than not, it’s a job that one chooses in order to support his or her family.

But policy makers continue to overlook this distinction and, in doing so, infringe upon sex workers’ rights and fundamental human rights. For example, in Cambodia, the 2008 Law on Suppression of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation and the severe stigma attached to doing adult sex work, have made it almost impossible for sex workers to access justice, healthcare and social security systems. The law has given rise to police raids on brothels where sex workers are “rescued” against their will. They are often retrained for jobs in low-wage garment factories and/or repatriated into their villages without access to the income they need to survive. “Rescue” by the police frequently exposes sex workers to more dangerous conditions in so-called rehabilitation centers. As one of our grantees put it, “What do you expect when a sex worker is ‘rescued’ by the most oppressive arm of the state?”

In a sex workers’ union office in Phnom Penh, a banner pinned to the wall reads, “Don’t talk to me about sewing machines. Talk to me about workers’ rights”—a clear message that interventionists need to rethink their approach.

A similar situation exists in Thailand where raids and “rescue operations” happen regularly. AJWS grantee EMPOWER created a Charlie Chaplin-style silent film that quite brilliantly depicts these “rescue operations.”

At the end of the day, the distinction between sex trafficking and sex work is clear. But the question remains: which policies will most effectively safeguard trafficking victims without exposing sex workers to harm? It’s simple, really. An AJWS grantee put it quite succinctly: “Nothing about us, without us.” If we intend to develop policies that are fair and just, we must solicit input from sex workers themselves.

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.