Before setting out to march in the Dominican Day Parade in New York City on Sunday, organizers of We Are All Dominican (WAAD)—a U.S.-based human rights organization supported by AJWS that fights to raise awareness about the controversial citizenship crisis unfolding in the Dominican Republic—issued a warning to their participants: Don’t lose your composure around hecklers, and use the buddy system if you feel uncomfortable and must step away from the group.

This advice might seem surprising at an event known to be a joyous celebration of Dominican culture in America and worldwide, but WAAD’s pointed message drew some boos and jeers last year. This time, they came prepared.

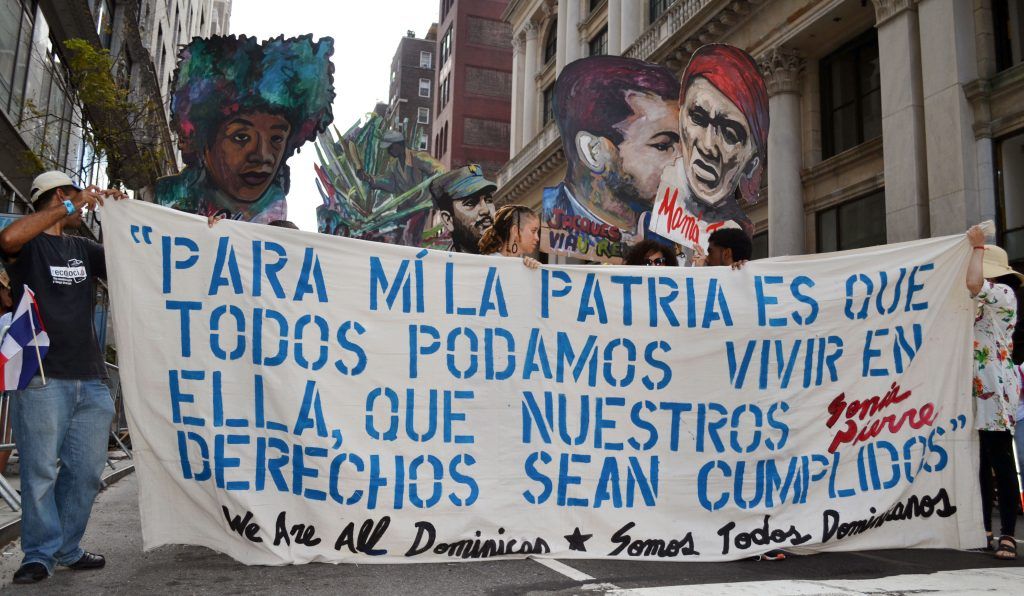

WAAD activists at the Dominican Day Parade in New York City

WAAD’s goal at the parade was to spread awareness about the plight of families being torn apart by a 2013 Dominican constitutional court decision to make retroactive the elimination of birthright citizenship for anyone born after 1929. The decision, which primarily affects Dominicans whose parents or even grandparents migrated from neighboring Haiti, has rendered more than 200,000 people “stateless”—not considered a national of any country in the world. The court ruling was followed by a new emphasis on deportations for Haitian migrants, which sent about 100,000 people fleeing across the Haitian border to makeshift tent camps and left countless Dominicans of Haitian descent who had not yet acquired documentation in fear of deportation.

In 2014, the Dominican government passed a new law touted as a solution to the issues raised by the court decision—but it only worsened the situation, dividing Dominicans of Haitian descent into two groups based on documentation and requiring the undocumented ones to register as “foreigners.” The individuals with documentation did not have their citizenship automatically restored as promised, and most members of the other group could not afford to fully register or did not receive adequate information about doing so. Activists believe the law acted as a trap to identify undocumented residents and created a legal justification for long-standing discrimination and racism in the country. Some, like Ana Maria Belique of Dominican-based AJWS grantee Reconoci.do, say the whole citizenship crisis “feels like ethnic cleansing.”

A History of Tension and Racism

Haiti and the Dominican Republic share an island in the Caribbean, but the two countries have a complex history. Haiti’s military invasion and 22-year occupation of the Dominican Republic in the early 1800s still weighs on the collective consciousness of Dominican people. And for nearly a century, Haitians who have crossed the border in search of economic opportunities like sugarcane and banana plantation work have often been greeted with discrimination and prejudice—and, in some cases, violence. In 1937, the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered his army to kill Haitians in a massacre known as El Corte, or “the cutting,” claiming the lives of between 15,000 and 30,000 Haitians.

More recently, in 2013, Haitian migrants and Dominicans of Haitian descent faced increased violence in their communities, mass expulsions and arbitrary detentions carried out by Dominican armed forces, national police and immigration authorities. In the poor districts where they live, called bateyes, Haitians sugarcane cutters typically lack access to schools, clinics, employment, marriage and other public services.

Activists say that this history of oppression—and the recent citizenship crisis—have roots in racism. Dominicans, who strongly identify with light skin, Catholicism and the Spanish language, often see black Haitians as “other” and reject any black roots they themselves may have.

WAAD Brings the Citizenship Crisis to the NYC Stage

This devastating situation was far from the minds of most revelers who lined the New York City parade route, and so WAAD’s goal was to open the eyes of fellow Dominicans to the prejudice and mistreatment happening in their midst. Activists contend that propaganda coming out of the Dominican Republic sways the opinions of Dominicans, Dominican Americans and even U.S. officials on Dominican policies and that many aren’t aware of the damage being caused.

A WAAD member is called over by a spectator to answer questions about what the group is protesting.

WAAD is made up mostly of Dominican American graduate students—some with Haitian ancestry—who are immigrants or whose parents are immigrants. They’re the American counterpart of Dominican-based advocacy organization Reconoci.do, whom AJWS also supports. WAAD hopes to spread their message of inclusion to a broad and potentially influential group of the Dominican diaspora in New York City. About 1.7 million Dominican expatriates—about 10 percent of the country’s population—live in the United States and can vote in both countries’ elections.

WAAD has been met with a range of dissent from these immigrants at protests it has staged around the city in recent years: People who don’t like their message of equality for Haitian-Dominicans say that WAAD members are not real Dominicans, they don’t know what they’re talking about, they’re traitors, they’re “fusionistas” trying to merge the Dominican Republic with neighboring Haiti—or they’re Haitians. “As if that’s an insult,” commented WAAD member Yanilda González. “These are standard rhetorical tactics used by people to delegitimize groups they don’t agree with.”

Unfazed by ongoing opposition and the backlash during last year’s Dominican Day Parade, WAAD decided to seize their “moment of biggest exposure” and march again this year. The small-but-mighty WAAD group of about 15 people represented their cause with pride—and resilience, on one of the hottest days of the summer—dancing, blowing whistles, waving Dominican and Haitian flags, chanting phrases like “Black lives matter—from New York to Santiago!” and displaying hand-painted cardboard signs featuring Dominican activists like the late Sonia Pierre, founder of longtime AJWS grantee MUDHA, which defends Haitian immigrants and their descendants living in bateyes. WAAD members hail Pierre as the “godmother” of the nationality struggle.

They also honored Jacques Viau Renaud, a Haitian-born Dominican revolutionary poet who was killed resisting the U.S.’s invasion of the D.R. in 1965; Gregorio Luperón, an ethnic Haitian who fought for the Dominican Republic’s independence in the 1860s; Mama Tingo, a Dominican activist assassinated while defending her rural community’s land rights in the 1970s; Francisco Caamaño, a democracy activist executed in the 1970s; and Haitian sugarcane workers, who are often described as modern slaves by human rights advocates.

WAAD members showcased hand-painted cardboard signs featuring Dominican activists.

The group was accompanied by Ana Maria Belique, coordinator of Reconoci.do, which has mobilized thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent to lobby for the Dominican government to recognize the rightful citizenship of Dominicans of Haitian descent. Reconoci.do has strived to influence the public dialogue on racism and nationality and to stem the xenophobia that has deepened since the Dominican court’s citizenship-stripping decree.

Belique said she was “happy to see Dominicans living abroad who empathize with this issue. This is very important for us who are in the Dominican Republic. It’s a morale booster for those of us doing the work in the country.

“It makes us feel that we’re connected to other groups and we’re not alone,” she continued. “It’s also important to note that there’s a lot of young people here, and we’re working for social change.”

“Celebrating Our Blackness”

As they marched, participants expressed a desire to raise awareness and educate people about what they call severe racial injustices occurring in the Dominican Republic.

“I think that celebration of a culture or a country should also acknowledge that there are inequalities in a society,” said Sabine Williams, a Haitian-American academic who recently got involved with WAAD. She echoed a sentiment shared by many human rights activists involved in the citizenship crisis that race plays a significant role in Dominicans discriminating against people of Haitian descent.

Marching in the parade, she said, is “a really important show of solidarity and an emphasis on the fact that there’s a denial of significant black populations pretty much everywhere.”

Stephanie Fernandez, a member of a Dominican group that celebrates afro-textured hair and who briefly walked with WAAD at the parade, heralded WAAD’s participation. “It’s so needed,” she said. “We cannot celebrate Dominicans without celebrating our blackness. I don’t think the conversations have taken place sufficiently. We need more spaces, visibility and dialogue.”

Navigating a Complex Legal System

Felix Cepeda, who has gone back and forth between the Dominican Republic and the U.S. his whole life, has also observed ignorance and racism among Dominicans against blacks in both countries. A member of Reconoci.do, he says groups like his have begun to make a difference through publicity campaigns, advocacy to soften discriminatory laws, and by mobilizing Dominicans of Haitian descent to learn their rights.

Felix lamented the complex new system of bureaucracy now required of any Dominicans of Haitian descent who hope to remain in the country. With Reconoci.do, he helps find solutions for the group of residents who don’t have documents and also supports those groups who do have documents to access identification cards and register to vote.

“Thanks to [Reconoci.do], I think thousands of people are getting access to documents,” he said. “But there’s a long way to go. The long-term issue is changing people’s minds and hearts so people understand that these are our brothers and sisters.”

Spectators at the Dominican Day Parade cheer for WAAD activists

Making People Think and Act

Felix is well-respected among his friends in the Dominican Republic for his social justice work helping the homeless with another organization. But one friend always asks him to change his Reconoci.do shirt. “To him, I’m supporting the invasion of Haitians,” he explained, referring to a reportedly common fear harbored by Dominicans that Haitians will take over their country.

He was thrilled to have the freedom to celebrate the true diversity of the Dominican Republic at the New York parade, which welcomes all Dominicans, no matter their race or country of origin. From what he’s observed, he said Haitians could never march in a parade in Santo Domingo because they’re scared of being harassed. “Being able to do this in the U.S. makes me think of the D.R., where people don’t have the right to celebrate who they are,” he said. “I hope this makes people think and hopefully act.”

WAAD supporter Nina Paulino, a U.S. immigrant from the D.R., said she keeps thinking about her children when she thinks about the citizenship crisis in the Dominican Republic. She wants people to imagine what it would be like if the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a similar ruling revoking citizenship that had already been granted to people from a particular region or racial or ethnic group. “Put yourself in these people’s shoes. A lot of [Dominicans] feel it’s OK” to allow discrimination to occur.

She called bateyes “inhumane” and decried the similarities to Trujillo’s dictatorship. “It’s unfortunate that here in 2016, we’re still having to denounce these [kind of things],” Nina said. “We’re going to speak up and keep denouncing. We’re here to support and scream if we have to.”

The WAAD banner reads: “Para mí la patria es que todos podamos vivir en ella, que nuestros derechos sean cumplidos,” which translates to, “For me, the homeland is that everyone can live in it and that the rights of all are respected.” This is a quote from Sonia Pierre, founder of longtime AJWS grantee MUDHA, which defends Haitian immigrants and their descendants living in bateyes.

Chris Nunez, a Dominican American WAAD member who has traveled to the Dominican Republic to see bateyes and sit in on community meetings, sees massive potential in drumming up support for WAAD’s ideals among the Dominican diaspora. “The U.S. and the D.R. are just so intertwined with migration—especially here in New York City,” he said. “Educating us as Americans on the issues going on with our brothers and sisters on the island is important. It gives WAAD a voice for folks who don’t fully understand it or have one way of looking at the issue.

“I’m not a believer in borders,” he continued, explaining what drives him to fight for justice. “People are human beings first. There are people in the D.R. who have been citizens for generations who are [suddenly not afforded the same rights] and fearful of going about their daily lives.”

By the end of the parade, it was safe to say WAAD got a different reaction from the crowd than they did last year. Several groups cheered for them, spectators called a WAAD member over to hear more about what the organization stands for, and a New York-based Dominican television station interviewed a member. Perhaps Ana Maria’s pre-parade pep talk—“We alone cannot make a change, but together collaborating, we can make a change”—influenced the day’s events.

AJWS will continue to support and stand in solidarity with groups like WAAD, Reconoci.do and MUDHA, in the hope that this movement will ultimately convince the Dominican government to reverse its hateful decree against the minority in its midst. Together, we stand with Dominicans of Haitian descent and all those who experience discrimination, racism and hate around the world.

All photos by Angela Cave.

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.