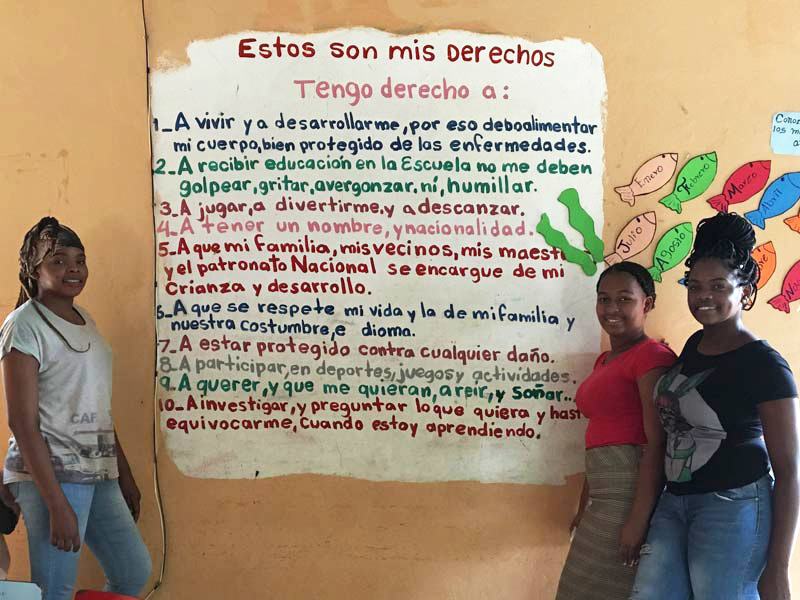

On a yellow wall, in a tiny school in the Dominican Republic, there is a sign—hand-painted in Spanish with cheery colors. It looks like the kind of sign you might find in any preschool, with a reminder of classroom rules—“Share your toys… Raise your hand… Don’t hit.” But instead, the sign reads: “These are my rights.”

It’s both an empowering and heartbreaking list of dignities and freedoms that all children should have, but none should have to be so aware that they lack:

I have the right to live and develop, to be protected from abuse of my body.

To receive an education in a school where I’m not beaten, yelled at, shamed, or humiliated.

To play, to have fun and to rest.

To have a name and nationality.

For my family, my neighbors, my teachers and the government to take care of my upbringing and my development.

To have my identity and our family customs and language respected.

To be protected against any harm.

To love and be loved, to laugh and to dream.

This sign and this school, called Escuela Anaisa, are located in the impoverished community Batey Palmerejo, a settlement on the urban outskirts of Santo Domingo. Formerly home to the workers at a sugarcane plantation that’s long since closed, the collection of structures sits crumbling and neglected—abutting rutted, muddy streets passable only on foot.

But poverty is not the only problem threatening these children’s future. Their classroom is adorned with rights, not youthful rules, because they are growing up without the basic freedoms guaranteed by citizenship.

They were born in the Dominican Republic—and so were many of their parents. But these kids and their families have long been denied the liberties granted to citizens by Dominican law. Many of their parents or grandparents migrated decades before from neighboring Haiti—typically with legal permits to work on the sugar cane plantations. But from the beginning, these migrants were treated as outsiders. Their children, born on Dominican soil, were entitled to birthright citizenship by the Constitution; but their Dominican identity was never acknowledged in practice. They faced powerful discrimination, were ostracized to communities with poor social services, and barred from well-paying jobs. They formed an oppressed “other” class denied both their Dominican identity and their humanity.

In 2013, the prejudice against Dominicans of Haitian descent took a new and very dangerous turn: The Dominican Constitutional Court issued a ruling that retroactively stripped the birthright citizenship of 133,770 members of this community—declaring them Haitian despite the fact that many had never set foot in Haiti. In an instant, they lost their nationality, suddenly stateless. They were now unable to legally work, vote, enroll their children in school, access health care or register their newborns as Dominican citizens.

The children I met at the Anaisa school are grappling with the fallout of this ruling—and the cycle of poverty this community has long faced. One of the teachers, Juliana, explained that many live with relatives or friends because their parents can’t care for them, and most come to school hungry because there isn’t enough money to put food on the table.

The Dominico-Haitian community is staggeringly under-resourced: The state refuses to provide funding for education, healthcare and other vital public services. Juliana described a tragic and not uncommon occurrence: “A woman in our community suffered a collapsed lung—and when her family called for an ambulance, they didn’t want to take her because she didn’t have Dominican ID. She died, leaving her children orphaned.”

But the Anaisa school offers a glimpse of hope. A grassroots organization that AJWS supports— Movimiento De Mujeres Domínico Haitiana (MUDHA)—runs the school, teaching approximately 150 local kids who would otherwise never have a chance to study. Along with the children, I met some young adults, Julieta and Scarlett, who grew up in the school and are now volunteering with MUDHA to teach the next generation—and members of the greater community—about their rights.

From the youngest age, they are teaching these kids that they are people deserving of respect and equality—which counters the prevailing message they’ve received from the Dominican government.

And while MUDHA is raising its students to have hope for a future without discrimination, its staff are tackling the citizenship crisis head-on. They’re litigating court cases in both national and international courts to help the descendants of Haitian migrants defend or acquire their right to nationality. They are also helping people navigate the existing maze of laws and policies to apply for and obtain identity documents.

This week, as we celebrate Human Rights Day, I am awed by the courage and determination of the staff at MUDHA to persevere despite the challenges stacked against them. I’m inspired by teachers who decorate their walls with rights—so that the next generation knows how they deserve to be treated and will be empowered to fight for justice when they grow up.

As Juliana, said: “We help our children understand that their worth is not measured by their nationality or their skin color. But by being a human being. As a human being, we are all worth the same in this land.”

AJWS’s work in countries and communities changes over time, responding to the evolving needs of partner organizations and the people they serve. To learn where AJWS is supporting activists and social justice movements today, please see Where We Work.